中庸之道 Golden Means

Bae Bien U, Kim Ho Deuk,

Sean Scully, Suh Yong Sun

Bae Bien U, Kim Ho Deuk,

Sean Scully, Suh Yong Sun

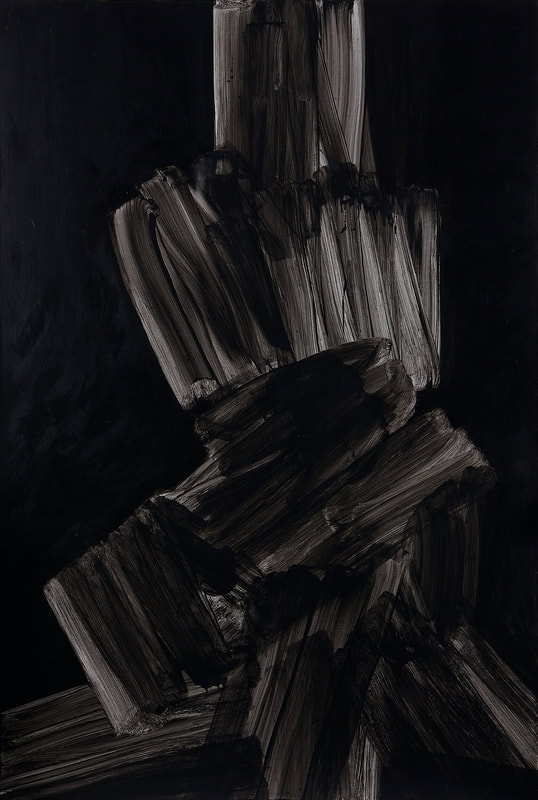

Kim Ho Deuk, 문득-서다 Just Stopped, 2020, 2023, Acrylic on canvas, 162.5x130.5cm

© Kim Ho Deuk

© Kim Ho Deuk

Kim Ho Deuk, 문득-서다 Just Stopped, 2020, 2023, Acrylic on canvas, 194x130.5cm

© Kim Ho Deuk

© Kim Ho Deuk

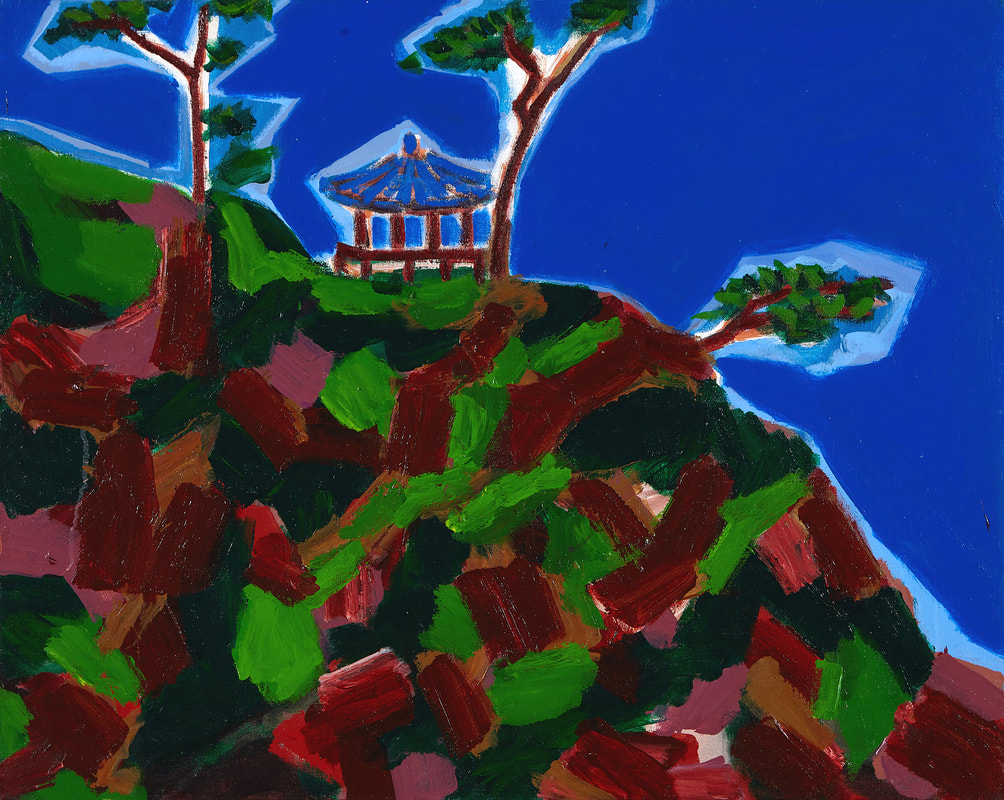

Suh Yong Sun, 팔당 1 Paldang 1, 2004, 2008, Oil on canvas, 80x100cm

© Suh Yongsun

© Suh Yongsun

Suh Yong Sun, 낙산사 1 Naksansa temple 3, 2009, Acrylic on canvas, 72.5x91cm

© Suh Yongsun

© Suh Yongsun

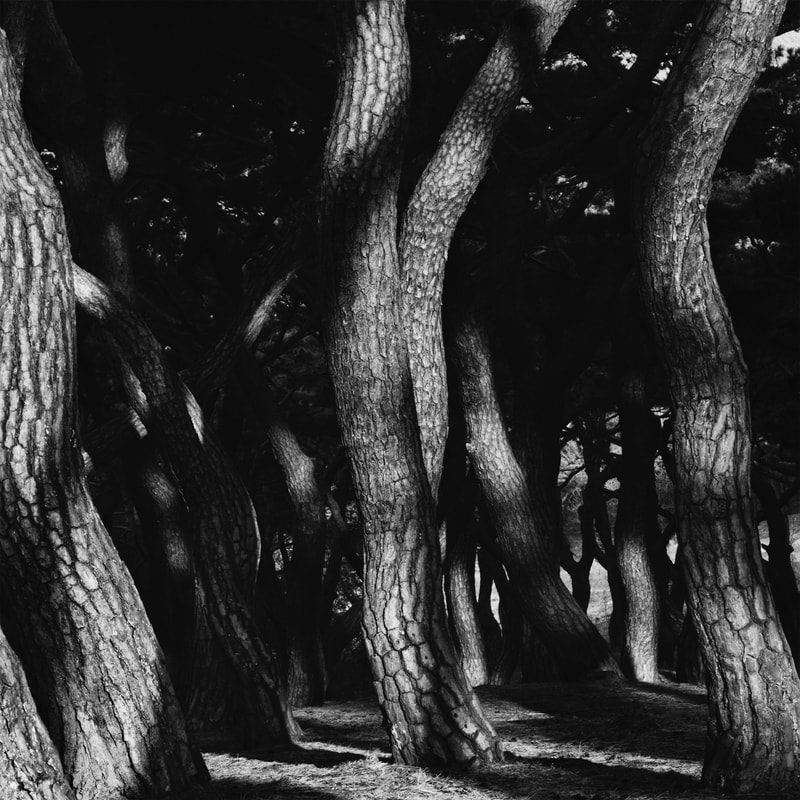

Bae Bien U, SNM3A-065, 2022, Gelatin silver Print, 125x125cm

© Bae Bien U; Courtesy Obscura

© Bae Bien U; Courtesy Obscura

Bae Bien U, SNM3A-029, 2015, Gelatin silver Print, 125x125cm

© Bae Bien U; Courtesy Obscura

© Bae Bien U; Courtesy Obscura

Sean Scully, Wall Blue Red, 10, 2022, Oil on linen, 71.1x81.3cm 28 x 32 in, (SCUL220025)

© Sean Scully; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

© Sean Scully; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Golden Means, Installation in Obscura, 2023

옵스큐라는 션 스컬리(Sean Scully), 김호득, 배병우, 서용선이 참가하는 “중용지도”를 오는 8월 30일 개최한다. 유학사상의 중요 개념 중 하나인 ‘중용’은 치우치지 않고 바뀌지 않는 것을 의미한다. 중용지도 전시는 점, 선, 면, 색 그리고 빛을 소재로 정중동(靜中動)에 위치한 작가와 그들이 선보이는 작업의 정수(精髓)를 선보인다. 국적과 문화를 넘어서 각기 다른 개성을 가진 4인의 작가들이 가진 중용의 에너지를 탐미하는 전시이다.

뜻대로 행해도 어긋나지 않는다는 종심(從心)[1]의 나이를 넘긴 작가들이 펼쳐내는 정제된 에너지를 옵스큐라는 ‘동시대성’의 한 형태로 제안한다. 중용지도 전시와 함께 발표되는 비평가 최정우의 「흑백의 색채, 부재의 존재, 비가시적인 것의 가시화 -동시대의 미학적 역사성의 최전선과 배수진: 다시 ’동시대’를 생각한다」는 본 전시의 기획 연구의 글이다. 그는 동시대성에 대해 “현재라는 단일하게 구성된 시간 안에서만 마치 느끼지 못하는 공기처럼 존재하듯 부재하는 것이 아니라, 과거와 현재와 미래를 여럿의 변증법적 틈과 그 틈들의 중첩적 시간들 속에서 매번 새롭게 다른 ‘지금’으로서 다시금 생각하고 느껴야 하는 것, 그래서 그렇게 거꾸로 부재하듯 존재하는 복수의 사태”로 정의하였다. 동시대를 단지 시간으로 구분하지 않는 것, 이 지점에서부터 중용지도의 동시대성은 시작한다. 김호득, 배병우, 서용선, 션 스컬리 작업에서 관객이 조우하는 초월적 교감은 동시대적이고 초시대적(超時代的)인 보편성이라 볼 수 있다.

중용지도 전시는 김호득, 배병우, 서용선, 션 스컬리의 12점 작업이 소개되며 10월 31일까지 옵스큐라 1에서 진행되며 관람은 예약제로 운영된다. ◼️옵스큐라

_______

[1] 공자(孔子)가 《논어論語)》 〈위정편爲政篇〉에서 "나이 일흔에 마음이 하고자 하는 대로 하여도 법도를 넘어서거나 어긋나지 않았다(七十而從心所欲 不踰矩)."고 한 데서 나이 일흔을 비유하는 말로 “종심”이 쓰였다.

Obscura will present an exhibition titled Golden Means, featuring artists such as Kim Ho Deuk, Bae Bien U, Suh Yong Sun, and Sean Scully on August 30th.

“Golden means (KR: 중용지도, hànzì: 中庸之道)” is a Confucian concept that equates excess with deficiency, thereby emphasizing the importance of balance or the tertium quid. The primary subject matter for all four artists is fundamental elements of the visual medium, namely, dots, lines, planes, colors, and light. The simple elegance created thereby belies their hard work, which remains inaccessible for the viewers. As such, the exhibition can be said to present the essence of their practice, an exploration of the spirit of golden means in the four idiosyncratic artists beyond the East-West binary.

Obscura exhibits the refined expression unfolded by artists who have experienced "Jongsim (hànzì: 從心)"[1] as a form of "Contemporaneity." Golden means and the essay by critic Choe Jeong U, titled Colors of Monochrome, Presence of Absence, and Visualization of the Invisible; The Front and Rear of Contemporary Aesthetic Historicism: Rethinking 'Contemporaneity,' serves as the conceptual research for this exhibition.

Choe mentioned about "Contemporaneity” as follow: The contemporaneity does not exist just like the air, which we take for granted as a homogeneously composed time unit called “present”, but exists as an event of plurality which is composed by various shapes and different phases of “now” that is absent as (in)existence in the multilayered dialectical gaps between past, present and future. The contemporaneity of Golden Meansdoesn't merely differentiate contemporaneity based on time. It initiates from this standpoint. The transcendent communion that the audience encounters in their works can be seen as contemporaneous and even pre-temporal universality.

Golden means shows a twenty works by Kim Ho Deuk, Bae Bien U, Suh Yong Sun, and Sean Scully at Obscura 1 until October 31. The exhibition is available by reservation only. ◼️Obscura

_______

[1] "It chases the heart," which stems from the fact that Confucius did not deviate from the Tao, even as he pursued his desires at the age of 70.

뜻대로 행해도 어긋나지 않는다는 종심(從心)[1]의 나이를 넘긴 작가들이 펼쳐내는 정제된 에너지를 옵스큐라는 ‘동시대성’의 한 형태로 제안한다. 중용지도 전시와 함께 발표되는 비평가 최정우의 「흑백의 색채, 부재의 존재, 비가시적인 것의 가시화 -동시대의 미학적 역사성의 최전선과 배수진: 다시 ’동시대’를 생각한다」는 본 전시의 기획 연구의 글이다. 그는 동시대성에 대해 “현재라는 단일하게 구성된 시간 안에서만 마치 느끼지 못하는 공기처럼 존재하듯 부재하는 것이 아니라, 과거와 현재와 미래를 여럿의 변증법적 틈과 그 틈들의 중첩적 시간들 속에서 매번 새롭게 다른 ‘지금’으로서 다시금 생각하고 느껴야 하는 것, 그래서 그렇게 거꾸로 부재하듯 존재하는 복수의 사태”로 정의하였다. 동시대를 단지 시간으로 구분하지 않는 것, 이 지점에서부터 중용지도의 동시대성은 시작한다. 김호득, 배병우, 서용선, 션 스컬리 작업에서 관객이 조우하는 초월적 교감은 동시대적이고 초시대적(超時代的)인 보편성이라 볼 수 있다.

중용지도 전시는 김호득, 배병우, 서용선, 션 스컬리의 12점 작업이 소개되며 10월 31일까지 옵스큐라 1에서 진행되며 관람은 예약제로 운영된다. ◼️옵스큐라

_______

[1] 공자(孔子)가 《논어論語)》 〈위정편爲政篇〉에서 "나이 일흔에 마음이 하고자 하는 대로 하여도 법도를 넘어서거나 어긋나지 않았다(七十而從心所欲 不踰矩)."고 한 데서 나이 일흔을 비유하는 말로 “종심”이 쓰였다.

Obscura will present an exhibition titled Golden Means, featuring artists such as Kim Ho Deuk, Bae Bien U, Suh Yong Sun, and Sean Scully on August 30th.

“Golden means (KR: 중용지도, hànzì: 中庸之道)” is a Confucian concept that equates excess with deficiency, thereby emphasizing the importance of balance or the tertium quid. The primary subject matter for all four artists is fundamental elements of the visual medium, namely, dots, lines, planes, colors, and light. The simple elegance created thereby belies their hard work, which remains inaccessible for the viewers. As such, the exhibition can be said to present the essence of their practice, an exploration of the spirit of golden means in the four idiosyncratic artists beyond the East-West binary.

Obscura exhibits the refined expression unfolded by artists who have experienced "Jongsim (hànzì: 從心)"[1] as a form of "Contemporaneity." Golden means and the essay by critic Choe Jeong U, titled Colors of Monochrome, Presence of Absence, and Visualization of the Invisible; The Front and Rear of Contemporary Aesthetic Historicism: Rethinking 'Contemporaneity,' serves as the conceptual research for this exhibition.

Choe mentioned about "Contemporaneity” as follow: The contemporaneity does not exist just like the air, which we take for granted as a homogeneously composed time unit called “present”, but exists as an event of plurality which is composed by various shapes and different phases of “now” that is absent as (in)existence in the multilayered dialectical gaps between past, present and future. The contemporaneity of Golden Meansdoesn't merely differentiate contemporaneity based on time. It initiates from this standpoint. The transcendent communion that the audience encounters in their works can be seen as contemporaneous and even pre-temporal universality.

Golden means shows a twenty works by Kim Ho Deuk, Bae Bien U, Suh Yong Sun, and Sean Scully at Obscura 1 until October 31. The exhibition is available by reservation only. ◼️Obscura

_______

[1] "It chases the heart," which stems from the fact that Confucius did not deviate from the Tao, even as he pursued his desires at the age of 70.

흑백의 색채, 부재의 존재, 비가시적인 것의 가시화

― 동시대의 미학적 역사성의 최전선과 배수진: 다시 ‘동시대’를 생각한다

왜 다시 동시대인가. 이것이 첫 번째 물음이다. 달리 말해 그저 ‘같은 시간대’라는 뜻의 동어반복을 넘어서 바로 이 ‘동시대’의 개념 안에서 새롭게 사유되고 실천되어야 할 것이 남아 있다면 그것은 무엇일 수 있으며 또 무엇이어야 하는가 하는 문제가 바로 이 물음의 정체이다. 하여 우리는 동시대 미술을 어떻게 규정해야 할까, 더 정확히 말해 ‘동시대의/라는 미술’을 어떻게 규정해야 할까. 이것이 두 번째 물음이다. 이 술어는 때로 좁게는 젊은 세대 예술가 군집의 등장과 반향을 가리키는 공시적으로 ‘중립적’인 규정이 되기도 하고, 때로 넓게는 생존 작가군 전체의 활동이나 경향을 뭉뚱그리는 통시적으로 ‘포괄적’인 규정이 되기도 한다. 그러나 동시대와 미술이 결합된 이 ‘동시대 미술’이라는 일견 중립적이고 포괄적인 술어가 어떤 특수한 미학적 역사성을 떠나서 생각될 수 없는 것이라고 할 때 이 ‘역사성’을 과연 어떻게 규정할 수 있는가 하는 문제가 또한 바로 이 물음의 정체가 된다. 그리고 마지막으로 동시대 예술은 무엇을 추구하며, 더 보편적으로는 여기서 우리가 예술의 ‘추구’라고 말하는 것은 과연 무엇인가. 이것이 세 번째 물음이다. 그렇게 이 마지막 물음은 다시 첫 물음과 이어진다. 곧 ‘동시대 미술’이라는 시공간적 규정이 단순한 감각적 선험성인 ‘시공간’으로서만 남아 있는 것이 아니라고 한다면, 바로 이러한 추구의 개념 속에서 드러나는 개인적인 동시에 집단적인 어떤 의지의 정체가 무엇인가, 이 문제가 다시금 이 물음들의 정체가 되며 또 그 정체가 동시대 예술의 사유와 실천의 문제를 다시금 되묻기 때문이다.

동시대란 그저 하나의 공유된 시간대를 의미하는 모호한 현대성을 의미하지 않는다. 무엇보다 그것은 단일적이거나 동일적인 것으로 묶일 수 없다. 동시대는 역설적이게도 언제나 복수적이며 이질적이다. 다시 말해, 동시대는 단 하나의 봉합된 시간 단위가 아니라 서로 겹치고 지워지면서 중첩된 여러 시간성들의 복수적이며 이질적인 효과이자 징후이다. 단일성과 동일성이 아니라 바로 이러한 복수성과 이질성을 어떻게 사유하고 실천할 수 있는가 하는 문제 안에 저 ‘동시대’라는 개념의 모든 정의와 사용설명서가 있다고 말해야 한다. 동시대는 어쩔 수 없이 무엇보다 하나의 시간성(temporalilty)을 전제하지만, 그 시간은 역설적이게도 ‘하나의 같은’ 시간이 아닌 ‘여럿의 다른’ 시간들, 곧 동(同)‐시대가 아니라 각자 다른 역사적 지층들을 중첩시키고 비켜나가며 다시 쌓아 흐트러뜨리는 간(間)‐시대성이며, 오직 그렇게 동시대성이 단순히 같은 시간대의 물리적 공유가 아니라 ‘사이[間]’의 변증법적 시간들과 그 시간들의 중첩으로 이해될 때에만, 예술의 시간과 역사는 하나의 ‘동(同/動)‐시대’로서의 현‐대성(con-temporality)이 된다는 역설, 바로 그로부터 동시대의 시간성은 새롭게 정의되고 실천되어야 한다. 그렇기에 동시대성이란 바로 현재라는 단일하게 구성된 시간 안에서만 마치 느끼지 못하는 공기처럼 존재하듯 부재하는 것이 아니라, 과거와 현재와 미래를 여럿의 변증법적 틈과 그 틈들의 중첩적 시간들 속에서 매번 새롭게 다른 ‘지금’으로서 다시금 생각하고 느껴야 하는 것, 그래서 그렇게 거꾸로 부재하듯 존재하는 복수의 사태이다. 그 풍경은 어둡고 희미하지만, 그래서 언제나 형체 없이 흐릿하게 보이지만, 바로 그 비가시성의 시선 안에서 역설적으로 더욱 분명하게 드러나는 것은 그 모든 시간성들의 틈과 결이다.

마치 중첩된 나무들과 그에 새겨진 여러 시간의 틈과 결이 그러하듯. 우리에게 보이는 단일한 화면 속 현재라는 단일한 시간의 허상에 속지 말고, 바로 그 현재가 부재하듯 존재하게 만드는 그 껍질들 사이로 아로새겨진 다양한 시간성과 그 위에 역사처럼 새겨진 보이지 않는 나이테와 속 깊은 상처를 바라보는 것. 아마도 이것이 동시대를 하나의 동일한 ‘시간’으로 이해하지 않고 여럿의 이질적인 ‘행위’이자 ‘윤리’로 이해하는 방식이 아닐까. 예를 들어 배병우의 시선이 그러하듯. 그러므로 그 ‘시선(視線)’이란 무엇보다 바로 이 단어 안에 포함된 가시성의 시각과 일직선의 시간을 넘어서 이해되고 실행되어야 하는 무엇이다.

이탈리아의 철학자 조르조 아감벤(Giorgio Agamben)은 동시대인을 “그 자신의 시대가 지닌 빛이 아니라 반대로 그 어둠을 인식하기 위해 바로 그 시대에 시선을 고정하는 이”1)라고 정의내린 바 있다. 그러므로 진정한 동시대성이란, 시쳇말처럼 시대의 흐름을 따른다는 식의 순응적 시간성과는 반대로, 역설적이게도 그 자체로 이질적인 부조화의 반시대성을 포함하고 있을 수밖에 없다. 왜냐하면 동시대성이란 시대와의 화합이 아닌 시대와의 불화, 시의적절한 것이 아닌 시대착오적인 것, 그래서 자신에게 주어진 시간의 단일성을 따르는 것이 아닌 바로 그 시간을 거슬러 그 시간 속에서는 비가시적인 복수의 이질성들을 가시화하는 것일 수밖에 없기 때문이다. 뻔히 보이는 시간의 단일한 빛이 아니라 바로 그 빛 때문에 오히려 보이지 않고 있는 여러 어둠들을 바라보고 그 어둠들을 비가시성으로부터 해방시키는 것, 그것이야말로 동시대 미술의 어떤 윤리가 된다. 그렇기에 이러한 동시대성의 윤리와 그 규정에 관해 나 역시 일전에 이렇게 썼던 바 있다. “그러나 동시대인으로서의 시인은 바로 그러한 빛이 아니라 그 구획과 배타성이 미처 포획하지 못하는 보이지 않는 어둠을 인식하려는 자, 그리고 그 인식을 위해 우리 시대의 동시대성을 다양한 현재성의 이미지들로 직시하고자 하는 자이다. 거대한 빛이 봉합하여 하나의 통합적 총체로 제시하는 시간성을 바로 그 동시대의 균열들이라는 어둠 속 작은 불빛들의 직시를 통해 파괴하고 그 거짓 통합과 위선의 봉합에 대해 진정한 의미의 변증법적 시간을 되돌려주는 자, 바로 그것이 ‘시인’이라고도 불리는 동시대인의 정의이자 과제가 되는 것이다. […] 그러므로 역설적으로 동시대인의 모습은 어떤 시차(déphasage)와 시대착오(anachronisme)의 모습을 띨 수밖에 없다. 왜냐하면 바로 그 동시대인 자체가 하나의 근본적 타자, 급진적 시인일 수밖에 없기 때문이다. 왜냐하면 한 시대가 스스로 규정하고 제시하는 통합적 시대성의 빛으로 그 시대를 바라보는 것이 아니라, 언제나 어떤 격차들의 균열로서/써만 그 시대를 응시하며, 거의 들리지 않는 그 소리들을 들으며, 동시에 그 시대의 봉합적 시간이 담아내지 못하는 다양한 동시대적 시간성들을 ‘반시대적으로’ 생각하는 이야말로, 그러한 본원적 타자로서의 진정한 ‘동시대인’이기 때문이다. […] 그리고 정확히 바로 이러한 의미에서, 이 ‘시인’이라는 이름의 동시대인은 결국 그 자신의 ‘시대’와 ‘사회’가 속해 있는 미학적 지평과 감성적 지도의 구획들을 확인하고 그 경계선 너머의 어둠을 바라보고 불러오는 자, 되돌아올 수 없는 선을 넘는 자이자 다시 반복하여 다르게 되돌아오는 자, 그리하여 우리가 사유할 수 없는 것으로 여겨지던 것을 사유할 수 있는 것으로 바꾸는 자이다.”2)

그러므로 동시대 예술이란 어쩌면 역설적이게도 시대의 빛 때문에 보이지 않는 어둠들을 보이게 함으로써 그 어둠들의 다층적인 시간성을 여럿의 이질적 현재들로 가시화하는 전략이자 그 전장일지 모른다. 그러므로 여기서, 비록 이것이 또 다른 동어반복처럼 들릴지라도, 그 어둠이 무엇보다 아직 색채를 갖지 못한, 또는 이미 색채를 결여한, 하나의 흑백으로 나타난다는 사실은 의미심장하다. 또한 그 흑백이 물리적인 흑백이 아니라 그러한 어둠의 다층적인 색들을 머금고 있다는 사실은 그래서 더욱 의미심장하다. 그리고 바로 이로부터, 단순한 재료의 선택이나 이어져온 화풍의 전통 등의 표면적 규정을 떠나서, 저 ‘흑백’의 풍경을 이러한 어둠들의 다양한 복수적 현재성으로부터 파악하고 감상하며 실행해야 하는 이유가 생긴다. 어둠은, 그것이 빛을 빛이게끔 하는 타자인 한에서, 무엇보다 흑백이다. 하지만 이 흑백이란 단지 색채가 결여된 단색을 뜻하는 것이 아니라 차라리 그 어둠이 담고 있는 모든 색들의 중첩된 시간성이다(하여, 이러한 시간성을 또한 저 ‘동시대성’이라는 이름으로 불러볼까). 그러므로 이를 ‘흑백의 색채’라 불러볼까, 그 색채를 흑백처럼 내화(內化)하고 그 흑백을 색채처럼 외화(外化)하는 그 모든 시간들이라고 불러볼까. 마치 저 추사(秋史)의 <세한도(歲寒圖)>라는 전통에 기대고 있는 듯 보이나 그를 떠나/함께 지금 이곳의 흑백이라는 색채의 어둠을 재현하지 않고 재현하고 있는 서용선의 화면처럼, 그 소나무와 그 집과 그 인물이 어둠 속에서 웅크리며 뿜어내는 저 모든 흑백의 잔인한 색채들처럼.

그리하여 바로 이 동시대의 역사성, 이 변증법적 역사의 피는 검붉은 모노크롬, 흑백과 단색들의 회색빛으로, 동시에 바로 그 흑백의 어둠이 지닌 다양한 색채들로 나타난다. 나는 이것을 동시대의 보이지 않는 색채, 비가시적인 것을 가시화하는 맹점, 바로 그 맹인의 관점에서 비로소 온전히 드러나는 어둠의 시각이라고 말하고 싶다. 그래서 다시 한 번, 이러한 평온하고 안온한 듯 보이는 흑백이 불러오는 가장 강렬한 시각화는 단지 물리적인 단색의 효과만을 의미하는 것이 아니다. 그것을 차라리 ‘색채’라고 해도 좋은 이유이다. 검고 흰 빛으로만 보이는 피의 색깔은 사실은 붉다. 그리고 어쩌면 그 피의 보이지 않는 붉은색을 드러내는 것이 동시대 미술의 가시적 흑백이라고 말해도 좋을 것이다. 동시대 예술가가 단지 문학이라는 좁은 장르에서만 쓰이는 명명을 넘어 모두 ‘시인’이 될 수 있고 또 ‘시인’이 되어야 한다는 것은 바로 이렇게 이해된 동시대의 윤리, 흑백의 어둠으로 또 다른 빛의 색채를 드러내는 일, 곧 비가시적인 것의 가시화라는 미학적 혁명의 규정 때문이라고 말해야 한다. 하여 묻자면, 붉은 동백꽃이 지는 처연한 풍경 뒤로 왜 흑백의 칠정이 겹쳐 보이는가. 피어나는가, 사그라지는가. 하나의 꽃, 여럿의 나무, 평평하거나 울퉁불퉁한 땅과 산들, 하나의 혹은 여럿의 자연으로만 보이는 그곳에서 보이지 않게 드러나며 그럼으로써 비로소 부재의 가시화로서 보이게 되는 저 이질적 역사성들의 동시대란 무엇인가. 예를 들어 강요배의 이미지들이 그러하듯이, 그 이미지들이 바로 그 흑백의 이미지 자체로 묻고 있는 색채들의 빈칸, 바로 그 빈칸이라는 의문부호처럼, 그렇게 그 화면들이 보이지 않는 것으로 보여주는 어떤 비가시성의 세계처럼, 그리고 바로 거기에 부재하듯 묻어 있고, 그래서 그렇게 비가시성의 가시적 형태로 잔존하는 어떤 비(非)‐존재처럼.

그러므로 이 흑백의 시로부터 출발하자면, 동시대 미술은 무엇보다 그 자신을 그렇게 하나의 ‘시’로서 발언하는 시각이다. 하여 동시에 역설적으로 이렇게 말해야 한다, 그 ‘시’의 발언이란 곧 말할 수 없는 것에 대한 말함이라고, 시는 언제나 시가 될 수 없는 것을 발언하는 역설과 이질성의 방식이라고. 시는 언제나 시의 반대이다, 마치 동시대성이 언제나 바로 그 자신의 시대와 불화하듯이. 예술이 발언하는 피의 풍경인 미학의 역사는 어쩌면 응어리졌기에 발언될 수 없었고 또 발언될 수 없는 모든 것들, 곧 말할 수 없는 것이 스스로 말없이 말할 수 있게 함을 추구해왔는지도 모른다. 말할 수 없기에 말할 수 없는 것을 보여주기, 아마도 그것이야말로 예술의 ‘발언(發言)’이 아니겠는가. 언어의 영역을 벗어난 삶과 역사의 비극, 그 언어화될 수 없는 사건/시간들을 비언어로써, 곧 더 나아가 말이 될 수 없기에 보이지 않는 것으로 남아 있는 것을 보이게 하는 힘, 시각화되지 못하는 것들을 시각화하는 힘, 그래서 곧 비가시적인 것들이 지닌 가시성의 힘을 드러내는 것, 그것이 바로 저 새롭게 정의된 ‘동시대성’의 예술이 말없이 말하는 모든 역사성의 근원 없는 근원이 아닐까. 그러므로 그러한 예술의 발언이란 언어화되지 못하는 것을 언어화하는 방식, 채 말이 되지 못한 것을 말로 드러나게 하는 방식, 그러나 동시에 더욱 역설적이게도 언어도 아니고 말조차 되지 못하는 비가시적 시각의 형태로 그 말 아닌 말, 언어 아닌 언어를 드러내는 방식은 아니겠는가. 마치 김호득의 파열들이 그러하듯. 이 말을 우리는 발언할 수 있을까, 그래서 어쩌면 이 ‘그림’이 보여주는 것은 어떤 말이 아니라 바로 그 ‘말’ 자체의 가능성과 불가능성은 아니겠는가.

동시대의 미학적 역사성이 위치해 있는 곳은 이렇듯 바로 그 자신의 시대에 반시대적으로 의문을 제기하는 저 불가능성의 장소와 그 가능성의 조건이라는 처소에 다름 아니다. 그러므로 단순히 현대의 예술이 아닌 간‐시간성으로서의 동시대의 예술이란 바로 이러한 미학적/역사적 역설 위에 서 있지 않은가. 시각을 다루는 미술이 바로 비가시적인 것으로부터 그 근원과 중첩의 힘을 긷고 있다는 이 근본적인 역설, 곧 비가시성이라는 시각의 불가능성 바로 그 자체가 오히려 시각예술의 가능성의 가장 근본적인 조건이 된다는 역설. 동시대 예술이란 바로 이러한 역설로부터 출발하여 그 역설을 휘감아 돌아 다시금 이 역설로 귀환하는 시시포스(Σίσυφος)의 운동은 아닐 것인가. 그러므로 여기에서 우리의 최전선은 동시에 우리의 배수진이 된다. 예술적 전위라는 의미에서 소위 아방가르드(avant-garde)라는 일직선의 진보를 전제하는 역사적/예술사적 규정이 무의미해진 이 ‘동시대’에, 더 이상 예술의 전방과 후방, 전통과 진보라는 개념들의 구분법은 통용되지 못한다. 변증법적 중첩의 시간성으로 이해된 동시대성, 그리고 보이지 않는 존재의 운동에서 출발해 그 부재를 가시화하는 하나의 용기이자 결단으로 이해된 동시대성, 바로 그 시대의 예술에서는 최종의 배수진이 곧 전방을 대변하며 최전선의 시작이 곧 후방을 반영하기 때문이다. 우리는 이 형태를 하나의 형태로서 측정할 수 없다. 최전선이자 배수진이 끝나는 곳, 배수진이자 최전선이 시작되는 곳은, 단일한 시간대로서 존재하는 것이 아니라 이질적인 복수의 변증법적 시간들이 중첩되며 해체되는 역사의 비역사성 안에 부재하는 것이기 때문이다. 그 장소 없는 장소, 마치 김홍주의 형태 없는 형태가 그러하듯.

그러므로 이 출발선 없는 출발, 이 종착점 없는 종착에서 시작하는 것은 어떨까, 그렇게 시작하듯 끝나는 것은 어떨까. 흑백이 색체를 가지게 되는 순간, 그러나 여전히 그 보이지 않는 색채를 보이는 흑백으로 시각화할 수밖에 없는 부재의 역사성을 감지하는 순간, 또한, 바로 이 기이한 가시성과 비가시성의 역사성 안에서 서로 섞이면서 또한 분리되고 있는 다층적이고 중첩적인 시간들의 틈과 결, 그것이 만들어내는 현재가 아닌 현재, 그 모든 어둠들이 문득 가리키며 불현 듯 내다보고 있을 어떤 도래할 시간들을 예감하는 순간, 우리는 바로 이 순간들을 동시대라고 불러야 하지 않을까. 그리고 바로 그때 동시대 예술의 윤리란, 그 사유와 실천이란, 바로 이러한 흑백의 색채, 부재의 존재, 그 비가시성의 가시화에 있다고 해야 하지 않을까. 더 이상의 혁명은 불가능하다고 말하는 시대, 혁명이라는 말 자체가 이미 하나의 종료된 ‘역사’일 뿐인 시대, 이 ‘동시대’에, 여전히 우리가 바로 그 오래된 ‘동시대’라는 말을 웅얼거림의 (비)언어로나마 발언할 수 있다면, 그래서 그렇게 보이지 않게 된 또 다른 역사성의 여러 시간들을 마치 초혼처럼 불러내어 바로 지금 이곳에 현현하게 할 수 있다면, 그래서 여전히 우리가 미학적 ‘해방’이라는 말 아닌 말, 언어 아닌 언어, 시각 아닌 시각의 실현을 동시대인이자 시인으로서 마치 하나의 부재하는 ‘시’로서 존재케 할 수 있다면... 그것은 우리의 복합적 ‘동시대’라는 시간성들의 암실(暗室, camera obscura) 속에서 탄생을 예비하며 소멸을 예견하는 저 모든 미학적 역사성의 혁명적 순간들, 바로 그 변증법적 시간 속에 있는 것은 아니겠는가. 어쩌면 이배의 숯덩이들이 그러하듯이, 이러한 비가시적인 것의 가시화로서의 예술은, 불타오르는 바로 현재의 단일한 순간이 아닌, 그 불타오름의 이전과 이후를 모두 포함하고 있는 여러 시간들의 지층을 역설적 찰나로 드러내는 바로 이 ‘동시대’의 충동과 추구 안에 있을 것이기에, 그것은 그렇게 없음으로 인해 있을 것이며, 또한 바로 그 부재로 인해 드러날 존재, 비가시성 안에서 비로소 가시적인 것이 될 무엇이기에. ◼️襤魂 최정우

_______

1) Giorgio Agamben, Qu’est-ce que le contemporain ? [traduit par Maxime Rovere], Payot & Rivages, 2008, p.19.

2) 최정우, [드물고 남루한, 헤프고 고귀한 ― 미학의 전장, 정치의 지도], 문학동네, 2020, 73-74쪽.

Colors of Monochrome, Presence of Absence, and Visualization of the Invisible

-The front and the rear of contemporary aesthetic historicity: rethinking the contemporaneity

Why does the contemporaneity matter again? This is our first question. In other words, this can be translated into another question: if something still remains unthinkable and unpracticable, that is to be newly thought and practiced, within this concept of contemporaneity, beyond a mere tautology which means only “the same time”, what can it be and must it be? How can we define the identity of “contemporary art”, more precisely speaking, of “the art of contemporaneity”? So, this is our second question. Sometimes in a narrow sense, this predicate of being contemporary can be a synchronically neutral definition which designates the appearance and the resonance of a group of young generation artists, and sometimes in a larger sense, it can be a diachronically comprehensive term which includes the activities and the tendencies of all groups of living artists in the same period. But if we can say that this definition or term of “contemporary art” (a composition of these two words, “contemporary” and “art”) which seems so neutral and comprehensive cannot be thought without a certain aesthetic historicity, how to define this “historicity” will be one of our crucial questions. Finally, what does contemporary art pursue, or more universally and fundamentally, what does this “pursuit” of the art mean here, can be our third question. Like this, the last question returns to the first one and they become linked to each other. Briefly, because all these questions are about an individual and collective “will” of the art revealed in this concept of “pursuit”, if this space-time definition of “contemporary art” cannot simply indicate a sensibly a priori “space-time” in Kantian sense, and because they ask again much more deeply the meaning of theories and practices of contemporary art in our era.

The contemporaneity does not only mean a kind of modernity understood as an equally shared temporality. Above all, this concept of contemporaneity cannot be synthesized just as a singular and homogeneous character. Paradoxically, it is always plural and heterogeneous. In other words, the contemporaneity is not a singular sutured unit of time, but rather a multilayer of plural and heterogeneous effects or symptoms in which various and different temporalities overlap and erase themselves. The possibility of definition of this “contemporaneity” does not reside in how to explain its unity and homogeneity, but in how to use its plurality and heterogeneity. It is inevitable to suppose a certain temporality to explain the concept of contemporaneity, but paradoxically, its time is not the same singular one but proposes different plural ones. Therefore, it is not a con-temporality but rather an inter-temporality, which overlaps, dislocates, rebuilds and scatters various historical strata, and in this only sense, so to speak, only when the concept of contemporaneity is understood not as a physically shared unit of time but as a dialectical time of gaps and as their multilayered temporalities, the time and the history of art can achieve its “con-temporality”. It is a kind of fundamental paradox, but starting from this point, we have to try to redefine and practice the temporalities of contemporaneity. Therefore, the contemporaneity does not exist just like the air, which we take for granted as a homogeneously composed time unit called “present”, but exists as an event of plurality which is composed by various shapes and different phases of “now” that is absent as (in)existence in the multilayered dialectical gaps between past, present and future. Its landscape seems so vague and hazy without its exact form, but what is revealed, paradoxically but evidently, visible in the very form of this invisibility, is the crack or the texture of all these temporalities.

Just like all the cracks and textures engraved in these overlapped trees. Not to be deceived by the illusions given in a singular moment within a singular frame in front of us, but to gaze at the deep stigmata of plural temporalities embodied in their grains and growth rings which make the presence absent and the absence present. Maybe this is how to understand the contemporaneity as various and heterogeneous “action” and also as a kind of “ethics” at the same time, not as a unique temporality. For example, just like the gaze of Bae Bien-U. So, this “gaze” is above all what has to be understood and practiced beyond a mere visibility and a simple linearity in this very word.

Giorgio Agamben defined the contemporary as “the one who fixes the gaze on his or her time not to perceive its lights but its darkness (celui qui fixe le regard sur son temps pour en percevoir non les lumières, mais l’obscurité)”[1] In this sense, the veritable contemporaneity does not suppose a temporal conformity which follows the trend of time, but an untimely discord which is paradoxically heterogeneous in itself, because it is nothing else than a disharmony with its time, not a harmony, an anachronic moment, not a timely gesture, and so consequently a visualization of the plural heterogeneities invisible in its time, not following its unity but going against it. To witness - not a single light of time but - its darkness invisible because of the very light and to emancipate this darkness from its invisibility, this act becomes the very ethics of contemporary art. As I wrote before about this ethics and its definition like this: “the poet as a contemporary is the one who tries to perceive not the visible light but the invisible darkness which cannot be captured by the distinction and the exclusivity of light, and also the one who tries to understand the contemporaneity of our time as various images of present(s) for this kind of perception. The one who destroys an illusional unity of time synthesized and sutured by the huge light through the dim one of small fireflies which mean the cracks of con-temporality, and the one who gives back veritable dialectical temporalities to our time against a false synthetization and a hypocritical suture of plural times, it becomes a definition/justice and a task of the contemporary which is also called ‘the poet’. […] So, the contemporary reveals himself or herself as a parallactic or anachronic one, because there is no other way than to be a radical ‘other’, in other words, a radical ‘poet’, in order to be this kind of contemporary, and because only the one who gazes at his or her time through its parallax, not by a synthesized perspective defined and proposed in its trend, listens to its silent sounds, looks at its invisible shapes, and reflects on various untimely temporalities which are not seized by its sutured unity, deserves the name of contemporary as a fundamental ‘other’. […] And precisely in this sense, this contemporary named poet is finally the one who verifies the map of aesthetic/political horizon and sensible borderline to which his or her ‘time’ and ‘society’ belong, summons the darkness beyond it, passes the irreversible line, returns in reiterating the unrepeatable, and therefore changes thinkable all the things that are considered as unthinkable.”[2]

Hence, paradoxically again, the “contemporary art” may be a strategy - and also its battlefield - of visualizing the multilayered temporalities of darkness as diverse heterogeneous realities by making visible the invisible against the existing order of light in our time. Here, even though it sounds as another tautology, the fact that this darkness reveals itself as a black and white color, lack of colors, without any color, is significant. So, the fact that this black and white color is not only a physical monochrome but rather a multilayered color of the darkness, is much more significant. And from this point of view, apart from a simple choice of materials or an existing pictorial tradition, we have a good motivation to conceive, appreciate and practice this black and white landscape as various, plural and even colorful forms of realities of this darkness. The darkness is monochrome in itself, insofar as it is the ‘other’ that makes light become light, but this black and white color does not simply mean a monochrome one but rather an overlapped temporality of all colors that it contains in itself. (So, in this context, can we call again this temporality in the name of “contemporaneity”?) Can we call it “the color of monochrome”? Can we call it all the forms of temporality which externalizes the monochrome as a color and internalizes the colors as a monochrome at the same time? Just like the screen of Sô Yong-Sôn’s images which seems to lean on the pictorial tradition of Chusa Kim Jeong-Hui’s “Winter Landscape” but, apart from this tradition at the same time, represents the colors’ monochrome without representing the monochrome’s colors. Just like all these cruel colors of the monochrome which this pine tree, this house and this human figure show us in the darkness.

Here, the blood of this contemporary historicity as a dialectical history reveals itself in dark red monochrome and in its various colors of the darkness at the same time. I would like to call this “color” of monochrome an invisible color of contemporaneity, a blind point of visualizing the invisible, and a perspective which can be completely achieved in this very point of blindness. So, here once again, the most powerful and colorful visualization of this monochrome, which seems simply stable and peaceful at first sight, does not only mean the effect of a mere black and white color. It is rather a real color. The color of blood expressed only in monochrome, is red in fact. And maybe that’s the reason we can say that it is the visible monochrome of contemporary art that expresses the invisible color of this blood. The reason we can say that a “contemporary” artist can and must be above all a “poet”, beyond its narrowly literary definition, is that the ethics of contemporary art can and must be an expression of another light by the darkness of monochrome, in other words, an aesthetic revolution of visualizing the invisible. In this context, I would like to ask a simple question, but a complicated one at the same time: why are the various ressentiments of monochrome overlapped behind the landscape of falling camellia blossoms? Why do they bloom and fall? What is the contemporaneity of all this heterogeneous historicity which reveals itself unrevealed and is also present in absence, in the landscape where there seem to be only flowers, trees, curved lands and mountains, briefly, just the nature? For example, just like Kang Yo-Bae’s images. Just like a colorful question mark that they show us right in their shape of a monochrome blank, in their invisible world that makes themselves visible, and so in their visible form of this surviving non-present invisibility.

Therefore, restarting from this point of monochrome poem, the contemporary art is above all a point of view from which it declares itself as a ‘poem’. So, at the same time and paradoxically once again, we have to say that the declaration of this ‘poem’ is the utterance of a mutter or a murmur which cannot be a language. The poetry is always a form of paradox and heterogeneity which utters and declares what cannot be a poem. The poem is always contrary to itself, just as the contemporaneity is always in discord with its own temporality. The historical place of aesthetics as a bloody landscape where the art declares itself has pursued to utter visibly what cannot be uttered in the form of invisible murmur or mutter. Visualizing what cannot be a language as a non-verbal form, maybe it is the declaration of art, the utterance of con-temporality. This force of visualizing the invisible, all the tragedies of life and history beyond the realm of language, all the non-verbal events and times, and so all the things that remain non-verbal because they cannot be uttered, in other words, the visible force of the invisible, maybe it is the origin without origins of all the historicity that this newly defined contemporaneity gives us its word without words. Therefore, the declaration of “contemporary art” understood in this way can be paradoxically another way of expressing non-linguistic language in order to visualize the invisible which has to be finally visible. For example, just like the cracked non-verbal verbs in Kim Ho-Deuk’s images. What these ‘images’ show us is not a word but the possibility and the impossibility of the ‘word’ itself.

Like this, the place where the aesthetic historicity of contemporaneity is located is nothing else than the point where this contemporaneity continues to raise the untimely questions about its conditions of the (im)possibility while it is in discord with its own time. So, the contemporary art, not simply as a ‘modern’ one but as an ‘inter-temporal’ one, resides in this aesthetic/historical paradox. It is the paradox that the visible art has its own origin and its overlapped power in the invisibility. This invisibility as an impossibility of the visible becomes the most fundamental condition of visual possibility. Therefore, the contemporary art is a kind of Sisyphean labor which has to start from this paradox, embrace it, and return to it. Here, in this paradoxical concept of contemporaneity, our front also becomes our rear at the same time. The artistic distinction between the front and the rear, the tradition and the progress, is no more valid in our con-temporary period, when the point of view that supposes a certain historicity of linear development, for example, using the concept of avant-garde, is useless and non-sense. Because, in our era when the contemporaneity is understood as an overlapped dialectical temporality and as a decisive courage to visualize the absence of invisible movements, the front line of the art represents its rear and its rear reflects its front at the same time. We cannot define this form simply as a single form. The place where the front and the rear start and finish together at the same time is not a single unity of time but rather a point of non-historical historicity where plural and heterogeneous temporalities integrate and disintegrate themselves. So, this is a place without places, just like a form without forms in Kim Hong-Joo’s images.

So, why don’t we (re)start from this point without points, from this place without places, where there are (no) origins without any origin and (no) destinations without any destination? At the very moment when the monochrome obtains its colors, but at the same time, at the very moment when it is inevitable to perceive and to accept this absent historicity where we cannot help visualizing the invisible colors in the form of visible monochrome, and also at the very moment when we forefeel another coming time in which the darkness of our time will make another form of various presences of absence in the cracks of space-time texture in this bizarre relation between the visibility and the invisibility, we have to call and summon all these moments in the new name of contemporaneity. And at this very moment, we also have to say that the ethics of contemporary art (so, all its theory and praxis, too) depends on this color of monochrome, this presence of absence, and this (im)possibility of visualizing the invisibility. If we can still use this old word “contemporaneity”, even in utterance of mutter, in our “contemporary” period when people say that the possibility of revolutions exists no longer and the word “revolution” itself already became a finished “history”, and if we can still summon all the invisible historical temporalities like an event of evocation and make them all visible in front of us like an event of epiphany, so if we – as a contemporary and a poet at the same time - can still let the word “aesthetic revolution” - this wordless word, this non-verbal verb and this invisible visuality - be a ‘poem’ which is present in absence, visualized in the invisible… all the revolutionary moments will survive in the form of dialectical temporality, waiting for their own birth and death, in the camera obscura of our complex contemporaneity. Maybe just like Lee Bae’s lumps of charcoal. The contemporary art as a visualization of the invisible will live and die, not in a single moment of flaming present, but in the very pulse and pursuit which (re)present the various temporal strata of the front and the rear, the past and the future, as a paradoxical instant. This is what can be present in its absence and what can be revealed visible in its invisibility. ◼️Ramhon Choe Jeong U

_______

[1]Giorgio Agamben, Qu’est-ce que le contemporain ?, [traduit en français par Maxime Rovere], Paris : Payot & Rivages, 2008, p.19.

[2] Ramhon Choe Jeong U, Rarity in tatters, sublimity while wasting: the battlefield of aesthetics, the cartography of politics [in Korean], Seoul : Munhakdongne, 2020, pp.73-74.

― 동시대의 미학적 역사성의 최전선과 배수진: 다시 ‘동시대’를 생각한다

왜 다시 동시대인가. 이것이 첫 번째 물음이다. 달리 말해 그저 ‘같은 시간대’라는 뜻의 동어반복을 넘어서 바로 이 ‘동시대’의 개념 안에서 새롭게 사유되고 실천되어야 할 것이 남아 있다면 그것은 무엇일 수 있으며 또 무엇이어야 하는가 하는 문제가 바로 이 물음의 정체이다. 하여 우리는 동시대 미술을 어떻게 규정해야 할까, 더 정확히 말해 ‘동시대의/라는 미술’을 어떻게 규정해야 할까. 이것이 두 번째 물음이다. 이 술어는 때로 좁게는 젊은 세대 예술가 군집의 등장과 반향을 가리키는 공시적으로 ‘중립적’인 규정이 되기도 하고, 때로 넓게는 생존 작가군 전체의 활동이나 경향을 뭉뚱그리는 통시적으로 ‘포괄적’인 규정이 되기도 한다. 그러나 동시대와 미술이 결합된 이 ‘동시대 미술’이라는 일견 중립적이고 포괄적인 술어가 어떤 특수한 미학적 역사성을 떠나서 생각될 수 없는 것이라고 할 때 이 ‘역사성’을 과연 어떻게 규정할 수 있는가 하는 문제가 또한 바로 이 물음의 정체가 된다. 그리고 마지막으로 동시대 예술은 무엇을 추구하며, 더 보편적으로는 여기서 우리가 예술의 ‘추구’라고 말하는 것은 과연 무엇인가. 이것이 세 번째 물음이다. 그렇게 이 마지막 물음은 다시 첫 물음과 이어진다. 곧 ‘동시대 미술’이라는 시공간적 규정이 단순한 감각적 선험성인 ‘시공간’으로서만 남아 있는 것이 아니라고 한다면, 바로 이러한 추구의 개념 속에서 드러나는 개인적인 동시에 집단적인 어떤 의지의 정체가 무엇인가, 이 문제가 다시금 이 물음들의 정체가 되며 또 그 정체가 동시대 예술의 사유와 실천의 문제를 다시금 되묻기 때문이다.

동시대란 그저 하나의 공유된 시간대를 의미하는 모호한 현대성을 의미하지 않는다. 무엇보다 그것은 단일적이거나 동일적인 것으로 묶일 수 없다. 동시대는 역설적이게도 언제나 복수적이며 이질적이다. 다시 말해, 동시대는 단 하나의 봉합된 시간 단위가 아니라 서로 겹치고 지워지면서 중첩된 여러 시간성들의 복수적이며 이질적인 효과이자 징후이다. 단일성과 동일성이 아니라 바로 이러한 복수성과 이질성을 어떻게 사유하고 실천할 수 있는가 하는 문제 안에 저 ‘동시대’라는 개념의 모든 정의와 사용설명서가 있다고 말해야 한다. 동시대는 어쩔 수 없이 무엇보다 하나의 시간성(temporalilty)을 전제하지만, 그 시간은 역설적이게도 ‘하나의 같은’ 시간이 아닌 ‘여럿의 다른’ 시간들, 곧 동(同)‐시대가 아니라 각자 다른 역사적 지층들을 중첩시키고 비켜나가며 다시 쌓아 흐트러뜨리는 간(間)‐시대성이며, 오직 그렇게 동시대성이 단순히 같은 시간대의 물리적 공유가 아니라 ‘사이[間]’의 변증법적 시간들과 그 시간들의 중첩으로 이해될 때에만, 예술의 시간과 역사는 하나의 ‘동(同/動)‐시대’로서의 현‐대성(con-temporality)이 된다는 역설, 바로 그로부터 동시대의 시간성은 새롭게 정의되고 실천되어야 한다. 그렇기에 동시대성이란 바로 현재라는 단일하게 구성된 시간 안에서만 마치 느끼지 못하는 공기처럼 존재하듯 부재하는 것이 아니라, 과거와 현재와 미래를 여럿의 변증법적 틈과 그 틈들의 중첩적 시간들 속에서 매번 새롭게 다른 ‘지금’으로서 다시금 생각하고 느껴야 하는 것, 그래서 그렇게 거꾸로 부재하듯 존재하는 복수의 사태이다. 그 풍경은 어둡고 희미하지만, 그래서 언제나 형체 없이 흐릿하게 보이지만, 바로 그 비가시성의 시선 안에서 역설적으로 더욱 분명하게 드러나는 것은 그 모든 시간성들의 틈과 결이다.

마치 중첩된 나무들과 그에 새겨진 여러 시간의 틈과 결이 그러하듯. 우리에게 보이는 단일한 화면 속 현재라는 단일한 시간의 허상에 속지 말고, 바로 그 현재가 부재하듯 존재하게 만드는 그 껍질들 사이로 아로새겨진 다양한 시간성과 그 위에 역사처럼 새겨진 보이지 않는 나이테와 속 깊은 상처를 바라보는 것. 아마도 이것이 동시대를 하나의 동일한 ‘시간’으로 이해하지 않고 여럿의 이질적인 ‘행위’이자 ‘윤리’로 이해하는 방식이 아닐까. 예를 들어 배병우의 시선이 그러하듯. 그러므로 그 ‘시선(視線)’이란 무엇보다 바로 이 단어 안에 포함된 가시성의 시각과 일직선의 시간을 넘어서 이해되고 실행되어야 하는 무엇이다.

이탈리아의 철학자 조르조 아감벤(Giorgio Agamben)은 동시대인을 “그 자신의 시대가 지닌 빛이 아니라 반대로 그 어둠을 인식하기 위해 바로 그 시대에 시선을 고정하는 이”1)라고 정의내린 바 있다. 그러므로 진정한 동시대성이란, 시쳇말처럼 시대의 흐름을 따른다는 식의 순응적 시간성과는 반대로, 역설적이게도 그 자체로 이질적인 부조화의 반시대성을 포함하고 있을 수밖에 없다. 왜냐하면 동시대성이란 시대와의 화합이 아닌 시대와의 불화, 시의적절한 것이 아닌 시대착오적인 것, 그래서 자신에게 주어진 시간의 단일성을 따르는 것이 아닌 바로 그 시간을 거슬러 그 시간 속에서는 비가시적인 복수의 이질성들을 가시화하는 것일 수밖에 없기 때문이다. 뻔히 보이는 시간의 단일한 빛이 아니라 바로 그 빛 때문에 오히려 보이지 않고 있는 여러 어둠들을 바라보고 그 어둠들을 비가시성으로부터 해방시키는 것, 그것이야말로 동시대 미술의 어떤 윤리가 된다. 그렇기에 이러한 동시대성의 윤리와 그 규정에 관해 나 역시 일전에 이렇게 썼던 바 있다. “그러나 동시대인으로서의 시인은 바로 그러한 빛이 아니라 그 구획과 배타성이 미처 포획하지 못하는 보이지 않는 어둠을 인식하려는 자, 그리고 그 인식을 위해 우리 시대의 동시대성을 다양한 현재성의 이미지들로 직시하고자 하는 자이다. 거대한 빛이 봉합하여 하나의 통합적 총체로 제시하는 시간성을 바로 그 동시대의 균열들이라는 어둠 속 작은 불빛들의 직시를 통해 파괴하고 그 거짓 통합과 위선의 봉합에 대해 진정한 의미의 변증법적 시간을 되돌려주는 자, 바로 그것이 ‘시인’이라고도 불리는 동시대인의 정의이자 과제가 되는 것이다. […] 그러므로 역설적으로 동시대인의 모습은 어떤 시차(déphasage)와 시대착오(anachronisme)의 모습을 띨 수밖에 없다. 왜냐하면 바로 그 동시대인 자체가 하나의 근본적 타자, 급진적 시인일 수밖에 없기 때문이다. 왜냐하면 한 시대가 스스로 규정하고 제시하는 통합적 시대성의 빛으로 그 시대를 바라보는 것이 아니라, 언제나 어떤 격차들의 균열로서/써만 그 시대를 응시하며, 거의 들리지 않는 그 소리들을 들으며, 동시에 그 시대의 봉합적 시간이 담아내지 못하는 다양한 동시대적 시간성들을 ‘반시대적으로’ 생각하는 이야말로, 그러한 본원적 타자로서의 진정한 ‘동시대인’이기 때문이다. […] 그리고 정확히 바로 이러한 의미에서, 이 ‘시인’이라는 이름의 동시대인은 결국 그 자신의 ‘시대’와 ‘사회’가 속해 있는 미학적 지평과 감성적 지도의 구획들을 확인하고 그 경계선 너머의 어둠을 바라보고 불러오는 자, 되돌아올 수 없는 선을 넘는 자이자 다시 반복하여 다르게 되돌아오는 자, 그리하여 우리가 사유할 수 없는 것으로 여겨지던 것을 사유할 수 있는 것으로 바꾸는 자이다.”2)

그러므로 동시대 예술이란 어쩌면 역설적이게도 시대의 빛 때문에 보이지 않는 어둠들을 보이게 함으로써 그 어둠들의 다층적인 시간성을 여럿의 이질적 현재들로 가시화하는 전략이자 그 전장일지 모른다. 그러므로 여기서, 비록 이것이 또 다른 동어반복처럼 들릴지라도, 그 어둠이 무엇보다 아직 색채를 갖지 못한, 또는 이미 색채를 결여한, 하나의 흑백으로 나타난다는 사실은 의미심장하다. 또한 그 흑백이 물리적인 흑백이 아니라 그러한 어둠의 다층적인 색들을 머금고 있다는 사실은 그래서 더욱 의미심장하다. 그리고 바로 이로부터, 단순한 재료의 선택이나 이어져온 화풍의 전통 등의 표면적 규정을 떠나서, 저 ‘흑백’의 풍경을 이러한 어둠들의 다양한 복수적 현재성으로부터 파악하고 감상하며 실행해야 하는 이유가 생긴다. 어둠은, 그것이 빛을 빛이게끔 하는 타자인 한에서, 무엇보다 흑백이다. 하지만 이 흑백이란 단지 색채가 결여된 단색을 뜻하는 것이 아니라 차라리 그 어둠이 담고 있는 모든 색들의 중첩된 시간성이다(하여, 이러한 시간성을 또한 저 ‘동시대성’이라는 이름으로 불러볼까). 그러므로 이를 ‘흑백의 색채’라 불러볼까, 그 색채를 흑백처럼 내화(內化)하고 그 흑백을 색채처럼 외화(外化)하는 그 모든 시간들이라고 불러볼까. 마치 저 추사(秋史)의 <세한도(歲寒圖)>라는 전통에 기대고 있는 듯 보이나 그를 떠나/함께 지금 이곳의 흑백이라는 색채의 어둠을 재현하지 않고 재현하고 있는 서용선의 화면처럼, 그 소나무와 그 집과 그 인물이 어둠 속에서 웅크리며 뿜어내는 저 모든 흑백의 잔인한 색채들처럼.

그리하여 바로 이 동시대의 역사성, 이 변증법적 역사의 피는 검붉은 모노크롬, 흑백과 단색들의 회색빛으로, 동시에 바로 그 흑백의 어둠이 지닌 다양한 색채들로 나타난다. 나는 이것을 동시대의 보이지 않는 색채, 비가시적인 것을 가시화하는 맹점, 바로 그 맹인의 관점에서 비로소 온전히 드러나는 어둠의 시각이라고 말하고 싶다. 그래서 다시 한 번, 이러한 평온하고 안온한 듯 보이는 흑백이 불러오는 가장 강렬한 시각화는 단지 물리적인 단색의 효과만을 의미하는 것이 아니다. 그것을 차라리 ‘색채’라고 해도 좋은 이유이다. 검고 흰 빛으로만 보이는 피의 색깔은 사실은 붉다. 그리고 어쩌면 그 피의 보이지 않는 붉은색을 드러내는 것이 동시대 미술의 가시적 흑백이라고 말해도 좋을 것이다. 동시대 예술가가 단지 문학이라는 좁은 장르에서만 쓰이는 명명을 넘어 모두 ‘시인’이 될 수 있고 또 ‘시인’이 되어야 한다는 것은 바로 이렇게 이해된 동시대의 윤리, 흑백의 어둠으로 또 다른 빛의 색채를 드러내는 일, 곧 비가시적인 것의 가시화라는 미학적 혁명의 규정 때문이라고 말해야 한다. 하여 묻자면, 붉은 동백꽃이 지는 처연한 풍경 뒤로 왜 흑백의 칠정이 겹쳐 보이는가. 피어나는가, 사그라지는가. 하나의 꽃, 여럿의 나무, 평평하거나 울퉁불퉁한 땅과 산들, 하나의 혹은 여럿의 자연으로만 보이는 그곳에서 보이지 않게 드러나며 그럼으로써 비로소 부재의 가시화로서 보이게 되는 저 이질적 역사성들의 동시대란 무엇인가. 예를 들어 강요배의 이미지들이 그러하듯이, 그 이미지들이 바로 그 흑백의 이미지 자체로 묻고 있는 색채들의 빈칸, 바로 그 빈칸이라는 의문부호처럼, 그렇게 그 화면들이 보이지 않는 것으로 보여주는 어떤 비가시성의 세계처럼, 그리고 바로 거기에 부재하듯 묻어 있고, 그래서 그렇게 비가시성의 가시적 형태로 잔존하는 어떤 비(非)‐존재처럼.

그러므로 이 흑백의 시로부터 출발하자면, 동시대 미술은 무엇보다 그 자신을 그렇게 하나의 ‘시’로서 발언하는 시각이다. 하여 동시에 역설적으로 이렇게 말해야 한다, 그 ‘시’의 발언이란 곧 말할 수 없는 것에 대한 말함이라고, 시는 언제나 시가 될 수 없는 것을 발언하는 역설과 이질성의 방식이라고. 시는 언제나 시의 반대이다, 마치 동시대성이 언제나 바로 그 자신의 시대와 불화하듯이. 예술이 발언하는 피의 풍경인 미학의 역사는 어쩌면 응어리졌기에 발언될 수 없었고 또 발언될 수 없는 모든 것들, 곧 말할 수 없는 것이 스스로 말없이 말할 수 있게 함을 추구해왔는지도 모른다. 말할 수 없기에 말할 수 없는 것을 보여주기, 아마도 그것이야말로 예술의 ‘발언(發言)’이 아니겠는가. 언어의 영역을 벗어난 삶과 역사의 비극, 그 언어화될 수 없는 사건/시간들을 비언어로써, 곧 더 나아가 말이 될 수 없기에 보이지 않는 것으로 남아 있는 것을 보이게 하는 힘, 시각화되지 못하는 것들을 시각화하는 힘, 그래서 곧 비가시적인 것들이 지닌 가시성의 힘을 드러내는 것, 그것이 바로 저 새롭게 정의된 ‘동시대성’의 예술이 말없이 말하는 모든 역사성의 근원 없는 근원이 아닐까. 그러므로 그러한 예술의 발언이란 언어화되지 못하는 것을 언어화하는 방식, 채 말이 되지 못한 것을 말로 드러나게 하는 방식, 그러나 동시에 더욱 역설적이게도 언어도 아니고 말조차 되지 못하는 비가시적 시각의 형태로 그 말 아닌 말, 언어 아닌 언어를 드러내는 방식은 아니겠는가. 마치 김호득의 파열들이 그러하듯. 이 말을 우리는 발언할 수 있을까, 그래서 어쩌면 이 ‘그림’이 보여주는 것은 어떤 말이 아니라 바로 그 ‘말’ 자체의 가능성과 불가능성은 아니겠는가.

동시대의 미학적 역사성이 위치해 있는 곳은 이렇듯 바로 그 자신의 시대에 반시대적으로 의문을 제기하는 저 불가능성의 장소와 그 가능성의 조건이라는 처소에 다름 아니다. 그러므로 단순히 현대의 예술이 아닌 간‐시간성으로서의 동시대의 예술이란 바로 이러한 미학적/역사적 역설 위에 서 있지 않은가. 시각을 다루는 미술이 바로 비가시적인 것으로부터 그 근원과 중첩의 힘을 긷고 있다는 이 근본적인 역설, 곧 비가시성이라는 시각의 불가능성 바로 그 자체가 오히려 시각예술의 가능성의 가장 근본적인 조건이 된다는 역설. 동시대 예술이란 바로 이러한 역설로부터 출발하여 그 역설을 휘감아 돌아 다시금 이 역설로 귀환하는 시시포스(Σίσυφος)의 운동은 아닐 것인가. 그러므로 여기에서 우리의 최전선은 동시에 우리의 배수진이 된다. 예술적 전위라는 의미에서 소위 아방가르드(avant-garde)라는 일직선의 진보를 전제하는 역사적/예술사적 규정이 무의미해진 이 ‘동시대’에, 더 이상 예술의 전방과 후방, 전통과 진보라는 개념들의 구분법은 통용되지 못한다. 변증법적 중첩의 시간성으로 이해된 동시대성, 그리고 보이지 않는 존재의 운동에서 출발해 그 부재를 가시화하는 하나의 용기이자 결단으로 이해된 동시대성, 바로 그 시대의 예술에서는 최종의 배수진이 곧 전방을 대변하며 최전선의 시작이 곧 후방을 반영하기 때문이다. 우리는 이 형태를 하나의 형태로서 측정할 수 없다. 최전선이자 배수진이 끝나는 곳, 배수진이자 최전선이 시작되는 곳은, 단일한 시간대로서 존재하는 것이 아니라 이질적인 복수의 변증법적 시간들이 중첩되며 해체되는 역사의 비역사성 안에 부재하는 것이기 때문이다. 그 장소 없는 장소, 마치 김홍주의 형태 없는 형태가 그러하듯.

그러므로 이 출발선 없는 출발, 이 종착점 없는 종착에서 시작하는 것은 어떨까, 그렇게 시작하듯 끝나는 것은 어떨까. 흑백이 색체를 가지게 되는 순간, 그러나 여전히 그 보이지 않는 색채를 보이는 흑백으로 시각화할 수밖에 없는 부재의 역사성을 감지하는 순간, 또한, 바로 이 기이한 가시성과 비가시성의 역사성 안에서 서로 섞이면서 또한 분리되고 있는 다층적이고 중첩적인 시간들의 틈과 결, 그것이 만들어내는 현재가 아닌 현재, 그 모든 어둠들이 문득 가리키며 불현 듯 내다보고 있을 어떤 도래할 시간들을 예감하는 순간, 우리는 바로 이 순간들을 동시대라고 불러야 하지 않을까. 그리고 바로 그때 동시대 예술의 윤리란, 그 사유와 실천이란, 바로 이러한 흑백의 색채, 부재의 존재, 그 비가시성의 가시화에 있다고 해야 하지 않을까. 더 이상의 혁명은 불가능하다고 말하는 시대, 혁명이라는 말 자체가 이미 하나의 종료된 ‘역사’일 뿐인 시대, 이 ‘동시대’에, 여전히 우리가 바로 그 오래된 ‘동시대’라는 말을 웅얼거림의 (비)언어로나마 발언할 수 있다면, 그래서 그렇게 보이지 않게 된 또 다른 역사성의 여러 시간들을 마치 초혼처럼 불러내어 바로 지금 이곳에 현현하게 할 수 있다면, 그래서 여전히 우리가 미학적 ‘해방’이라는 말 아닌 말, 언어 아닌 언어, 시각 아닌 시각의 실현을 동시대인이자 시인으로서 마치 하나의 부재하는 ‘시’로서 존재케 할 수 있다면... 그것은 우리의 복합적 ‘동시대’라는 시간성들의 암실(暗室, camera obscura) 속에서 탄생을 예비하며 소멸을 예견하는 저 모든 미학적 역사성의 혁명적 순간들, 바로 그 변증법적 시간 속에 있는 것은 아니겠는가. 어쩌면 이배의 숯덩이들이 그러하듯이, 이러한 비가시적인 것의 가시화로서의 예술은, 불타오르는 바로 현재의 단일한 순간이 아닌, 그 불타오름의 이전과 이후를 모두 포함하고 있는 여러 시간들의 지층을 역설적 찰나로 드러내는 바로 이 ‘동시대’의 충동과 추구 안에 있을 것이기에, 그것은 그렇게 없음으로 인해 있을 것이며, 또한 바로 그 부재로 인해 드러날 존재, 비가시성 안에서 비로소 가시적인 것이 될 무엇이기에. ◼️襤魂 최정우

_______

1) Giorgio Agamben, Qu’est-ce que le contemporain ? [traduit par Maxime Rovere], Payot & Rivages, 2008, p.19.

2) 최정우, [드물고 남루한, 헤프고 고귀한 ― 미학의 전장, 정치의 지도], 문학동네, 2020, 73-74쪽.

Colors of Monochrome, Presence of Absence, and Visualization of the Invisible

-The front and the rear of contemporary aesthetic historicity: rethinking the contemporaneity

Why does the contemporaneity matter again? This is our first question. In other words, this can be translated into another question: if something still remains unthinkable and unpracticable, that is to be newly thought and practiced, within this concept of contemporaneity, beyond a mere tautology which means only “the same time”, what can it be and must it be? How can we define the identity of “contemporary art”, more precisely speaking, of “the art of contemporaneity”? So, this is our second question. Sometimes in a narrow sense, this predicate of being contemporary can be a synchronically neutral definition which designates the appearance and the resonance of a group of young generation artists, and sometimes in a larger sense, it can be a diachronically comprehensive term which includes the activities and the tendencies of all groups of living artists in the same period. But if we can say that this definition or term of “contemporary art” (a composition of these two words, “contemporary” and “art”) which seems so neutral and comprehensive cannot be thought without a certain aesthetic historicity, how to define this “historicity” will be one of our crucial questions. Finally, what does contemporary art pursue, or more universally and fundamentally, what does this “pursuit” of the art mean here, can be our third question. Like this, the last question returns to the first one and they become linked to each other. Briefly, because all these questions are about an individual and collective “will” of the art revealed in this concept of “pursuit”, if this space-time definition of “contemporary art” cannot simply indicate a sensibly a priori “space-time” in Kantian sense, and because they ask again much more deeply the meaning of theories and practices of contemporary art in our era.

The contemporaneity does not only mean a kind of modernity understood as an equally shared temporality. Above all, this concept of contemporaneity cannot be synthesized just as a singular and homogeneous character. Paradoxically, it is always plural and heterogeneous. In other words, the contemporaneity is not a singular sutured unit of time, but rather a multilayer of plural and heterogeneous effects or symptoms in which various and different temporalities overlap and erase themselves. The possibility of definition of this “contemporaneity” does not reside in how to explain its unity and homogeneity, but in how to use its plurality and heterogeneity. It is inevitable to suppose a certain temporality to explain the concept of contemporaneity, but paradoxically, its time is not the same singular one but proposes different plural ones. Therefore, it is not a con-temporality but rather an inter-temporality, which overlaps, dislocates, rebuilds and scatters various historical strata, and in this only sense, so to speak, only when the concept of contemporaneity is understood not as a physically shared unit of time but as a dialectical time of gaps and as their multilayered temporalities, the time and the history of art can achieve its “con-temporality”. It is a kind of fundamental paradox, but starting from this point, we have to try to redefine and practice the temporalities of contemporaneity. Therefore, the contemporaneity does not exist just like the air, which we take for granted as a homogeneously composed time unit called “present”, but exists as an event of plurality which is composed by various shapes and different phases of “now” that is absent as (in)existence in the multilayered dialectical gaps between past, present and future. Its landscape seems so vague and hazy without its exact form, but what is revealed, paradoxically but evidently, visible in the very form of this invisibility, is the crack or the texture of all these temporalities.

Just like all the cracks and textures engraved in these overlapped trees. Not to be deceived by the illusions given in a singular moment within a singular frame in front of us, but to gaze at the deep stigmata of plural temporalities embodied in their grains and growth rings which make the presence absent and the absence present. Maybe this is how to understand the contemporaneity as various and heterogeneous “action” and also as a kind of “ethics” at the same time, not as a unique temporality. For example, just like the gaze of Bae Bien-U. So, this “gaze” is above all what has to be understood and practiced beyond a mere visibility and a simple linearity in this very word.

Giorgio Agamben defined the contemporary as “the one who fixes the gaze on his or her time not to perceive its lights but its darkness (celui qui fixe le regard sur son temps pour en percevoir non les lumières, mais l’obscurité)”[1] In this sense, the veritable contemporaneity does not suppose a temporal conformity which follows the trend of time, but an untimely discord which is paradoxically heterogeneous in itself, because it is nothing else than a disharmony with its time, not a harmony, an anachronic moment, not a timely gesture, and so consequently a visualization of the plural heterogeneities invisible in its time, not following its unity but going against it. To witness - not a single light of time but - its darkness invisible because of the very light and to emancipate this darkness from its invisibility, this act becomes the very ethics of contemporary art. As I wrote before about this ethics and its definition like this: “the poet as a contemporary is the one who tries to perceive not the visible light but the invisible darkness which cannot be captured by the distinction and the exclusivity of light, and also the one who tries to understand the contemporaneity of our time as various images of present(s) for this kind of perception. The one who destroys an illusional unity of time synthesized and sutured by the huge light through the dim one of small fireflies which mean the cracks of con-temporality, and the one who gives back veritable dialectical temporalities to our time against a false synthetization and a hypocritical suture of plural times, it becomes a definition/justice and a task of the contemporary which is also called ‘the poet’. […] So, the contemporary reveals himself or herself as a parallactic or anachronic one, because there is no other way than to be a radical ‘other’, in other words, a radical ‘poet’, in order to be this kind of contemporary, and because only the one who gazes at his or her time through its parallax, not by a synthesized perspective defined and proposed in its trend, listens to its silent sounds, looks at its invisible shapes, and reflects on various untimely temporalities which are not seized by its sutured unity, deserves the name of contemporary as a fundamental ‘other’. […] And precisely in this sense, this contemporary named poet is finally the one who verifies the map of aesthetic/political horizon and sensible borderline to which his or her ‘time’ and ‘society’ belong, summons the darkness beyond it, passes the irreversible line, returns in reiterating the unrepeatable, and therefore changes thinkable all the things that are considered as unthinkable.”[2]

Hence, paradoxically again, the “contemporary art” may be a strategy - and also its battlefield - of visualizing the multilayered temporalities of darkness as diverse heterogeneous realities by making visible the invisible against the existing order of light in our time. Here, even though it sounds as another tautology, the fact that this darkness reveals itself as a black and white color, lack of colors, without any color, is significant. So, the fact that this black and white color is not only a physical monochrome but rather a multilayered color of the darkness, is much more significant. And from this point of view, apart from a simple choice of materials or an existing pictorial tradition, we have a good motivation to conceive, appreciate and practice this black and white landscape as various, plural and even colorful forms of realities of this darkness. The darkness is monochrome in itself, insofar as it is the ‘other’ that makes light become light, but this black and white color does not simply mean a monochrome one but rather an overlapped temporality of all colors that it contains in itself. (So, in this context, can we call again this temporality in the name of “contemporaneity”?) Can we call it “the color of monochrome”? Can we call it all the forms of temporality which externalizes the monochrome as a color and internalizes the colors as a monochrome at the same time? Just like the screen of Sô Yong-Sôn’s images which seems to lean on the pictorial tradition of Chusa Kim Jeong-Hui’s “Winter Landscape” but, apart from this tradition at the same time, represents the colors’ monochrome without representing the monochrome’s colors. Just like all these cruel colors of the monochrome which this pine tree, this house and this human figure show us in the darkness.

Here, the blood of this contemporary historicity as a dialectical history reveals itself in dark red monochrome and in its various colors of the darkness at the same time. I would like to call this “color” of monochrome an invisible color of contemporaneity, a blind point of visualizing the invisible, and a perspective which can be completely achieved in this very point of blindness. So, here once again, the most powerful and colorful visualization of this monochrome, which seems simply stable and peaceful at first sight, does not only mean the effect of a mere black and white color. It is rather a real color. The color of blood expressed only in monochrome, is red in fact. And maybe that’s the reason we can say that it is the visible monochrome of contemporary art that expresses the invisible color of this blood. The reason we can say that a “contemporary” artist can and must be above all a “poet”, beyond its narrowly literary definition, is that the ethics of contemporary art can and must be an expression of another light by the darkness of monochrome, in other words, an aesthetic revolution of visualizing the invisible. In this context, I would like to ask a simple question, but a complicated one at the same time: why are the various ressentiments of monochrome overlapped behind the landscape of falling camellia blossoms? Why do they bloom and fall? What is the contemporaneity of all this heterogeneous historicity which reveals itself unrevealed and is also present in absence, in the landscape where there seem to be only flowers, trees, curved lands and mountains, briefly, just the nature? For example, just like Kang Yo-Bae’s images. Just like a colorful question mark that they show us right in their shape of a monochrome blank, in their invisible world that makes themselves visible, and so in their visible form of this surviving non-present invisibility.

Therefore, restarting from this point of monochrome poem, the contemporary art is above all a point of view from which it declares itself as a ‘poem’. So, at the same time and paradoxically once again, we have to say that the declaration of this ‘poem’ is the utterance of a mutter or a murmur which cannot be a language. The poetry is always a form of paradox and heterogeneity which utters and declares what cannot be a poem. The poem is always contrary to itself, just as the contemporaneity is always in discord with its own temporality. The historical place of aesthetics as a bloody landscape where the art declares itself has pursued to utter visibly what cannot be uttered in the form of invisible murmur or mutter. Visualizing what cannot be a language as a non-verbal form, maybe it is the declaration of art, the utterance of con-temporality. This force of visualizing the invisible, all the tragedies of life and history beyond the realm of language, all the non-verbal events and times, and so all the things that remain non-verbal because they cannot be uttered, in other words, the visible force of the invisible, maybe it is the origin without origins of all the historicity that this newly defined contemporaneity gives us its word without words. Therefore, the declaration of “contemporary art” understood in this way can be paradoxically another way of expressing non-linguistic language in order to visualize the invisible which has to be finally visible. For example, just like the cracked non-verbal verbs in Kim Ho-Deuk’s images. What these ‘images’ show us is not a word but the possibility and the impossibility of the ‘word’ itself.

Like this, the place where the aesthetic historicity of contemporaneity is located is nothing else than the point where this contemporaneity continues to raise the untimely questions about its conditions of the (im)possibility while it is in discord with its own time. So, the contemporary art, not simply as a ‘modern’ one but as an ‘inter-temporal’ one, resides in this aesthetic/historical paradox. It is the paradox that the visible art has its own origin and its overlapped power in the invisibility. This invisibility as an impossibility of the visible becomes the most fundamental condition of visual possibility. Therefore, the contemporary art is a kind of Sisyphean labor which has to start from this paradox, embrace it, and return to it. Here, in this paradoxical concept of contemporaneity, our front also becomes our rear at the same time. The artistic distinction between the front and the rear, the tradition and the progress, is no more valid in our con-temporary period, when the point of view that supposes a certain historicity of linear development, for example, using the concept of avant-garde, is useless and non-sense. Because, in our era when the contemporaneity is understood as an overlapped dialectical temporality and as a decisive courage to visualize the absence of invisible movements, the front line of the art represents its rear and its rear reflects its front at the same time. We cannot define this form simply as a single form. The place where the front and the rear start and finish together at the same time is not a single unity of time but rather a point of non-historical historicity where plural and heterogeneous temporalities integrate and disintegrate themselves. So, this is a place without places, just like a form without forms in Kim Hong-Joo’s images.

So, why don’t we (re)start from this point without points, from this place without places, where there are (no) origins without any origin and (no) destinations without any destination? At the very moment when the monochrome obtains its colors, but at the same time, at the very moment when it is inevitable to perceive and to accept this absent historicity where we cannot help visualizing the invisible colors in the form of visible monochrome, and also at the very moment when we forefeel another coming time in which the darkness of our time will make another form of various presences of absence in the cracks of space-time texture in this bizarre relation between the visibility and the invisibility, we have to call and summon all these moments in the new name of contemporaneity. And at this very moment, we also have to say that the ethics of contemporary art (so, all its theory and praxis, too) depends on this color of monochrome, this presence of absence, and this (im)possibility of visualizing the invisibility. If we can still use this old word “contemporaneity”, even in utterance of mutter, in our “contemporary” period when people say that the possibility of revolutions exists no longer and the word “revolution” itself already became a finished “history”, and if we can still summon all the invisible historical temporalities like an event of evocation and make them all visible in front of us like an event of epiphany, so if we – as a contemporary and a poet at the same time - can still let the word “aesthetic revolution” - this wordless word, this non-verbal verb and this invisible visuality - be a ‘poem’ which is present in absence, visualized in the invisible… all the revolutionary moments will survive in the form of dialectical temporality, waiting for their own birth and death, in the camera obscura of our complex contemporaneity. Maybe just like Lee Bae’s lumps of charcoal. The contemporary art as a visualization of the invisible will live and die, not in a single moment of flaming present, but in the very pulse and pursuit which (re)present the various temporal strata of the front and the rear, the past and the future, as a paradoxical instant. This is what can be present in its absence and what can be revealed visible in its invisibility. ◼️Ramhon Choe Jeong U

_______

[1]Giorgio Agamben, Qu’est-ce que le contemporain ?, [traduit en français par Maxime Rovere], Paris : Payot & Rivages, 2008, p.19.

[2] Ramhon Choe Jeong U, Rarity in tatters, sublimity while wasting: the battlefield of aesthetics, the cartography of politics [in Korean], Seoul : Munhakdongne, 2020, pp.73-74.

김호득(b.1950, 대구, 한국)은 1986년 관훈미술관 개인전을 시작으로 수묵을 바탕으로 한 다양한 회화적 실험을 40여년간 선보이고 있다. 김호득(학고재, 서울, 2019), 산 산 물 물(갤러리 분도, 대구, 2018), ZIP – 차고, 비고(파라다이스 ZIP, 대구, 2017), 그냥, 문득(김종영 미술관, 서울, 2014) 등에서 개인전을 진행하였다. 그는 김수근문화상 미술상(김수근 문화재단, 서울, 1993), 토탈미술상(토탈미술관, 장흥, 1995), 이중섭미술상(조선일보사, 서울, 2003) 등을 수여 받았다. 국립현대미술관, 서울시립미술관, 삼성미술관, 대전시립미술관, 대구미술관, 금호미술관, 일민미술관, 호암미술관 등에 작품이 소장되어 있다. 그는 서울대학교 미술대학 회화과를 졸업하고 동대학원에서 동양화과 석사 학위를 받았다.

배병우(b.1950b, 여수, 한국)는 1982년 첫 개인전 이후로 국제적인 활동을 이어오고 있다. 2006년 아시아 사진작가로는 최초로 스페인 티션보르네미서 미술관(Thyssen Bornemisza Museum)에서 개인전을 열었고 스페인 정부의 의뢰로 세계문화유산인 알함브라궁전의 정원을 2년간 촬영하여 알함브라 궁전과 서울 덕수궁 미술관에서 순회 전시를 진행하기도 하였다. 이 밖에 광주시립미술관(2015), 프랑스 생테티엔 미술관(Musee d'art moderne de saint-etienne, France, 2015), 프랑스 국립재단 샹보르 성(Château de Chambord, France), 빌모트 재단(Wilmotte Foundation, 2022, Venice, Italy) 등에서 대규모 개인전을 열었다. 2016년 이중섭미술상과 2023년 프랑스 정부에서 문화예술공로훈장 슈발리에장을 수여 받았다. 그는 홍익대학교 미술대학 응용미술학과와 동대학원을 졸업하였다.

서용선(b.1951, 서울, 한국)은 밀도 있고 구축적인 평면과 도전적일 정도로 거친 질감의 표현을 통해 인간실존의 문제를 특유의 조형언어로 승화시킨다는 평을 받고 있다. 서용선: 내 이름은 빨강(아트선재, 서울, 2023), 서용선의 마고 이야기, 우리안의 여신을 찾아서(서울여성역사문화공간 여담재, 2021), 만첩산중 서용선 회화(여주미술관, 여주, 2021), 통증 ·징후 ·증세:서용선의 역사 그리기(아트센터화이트블럭, 파주, 2019), 확장하는 선, 서용선 드로잉(아르코미술관, 서울, 2016) 등에서 개인전을 진행하였다. 올해의 작가(국립현대미술관, 과천, 2009)에 선정되고 이중섭미술상(조선일보사, 서울, 2014) 등 다수의 상을 수여받았다. 2023년 가을 신안에 위치한 옛 암태농협창고에서 1920년대 항일운동인 ‘암태도 소작항쟁’ 100주년 벽화를 공개할 예정이다. 그는 서울대학교 미술대학 회화과를 졸업하고 동 대학원 서양화과에서 석사 학위를 받았다.

션 스컬리(Sean Scully, b.1945, Dublin, Ireland)는 1980년대 미국 뉴욕의 미니멀리즘 회화 운동에 반(反)하며 자유로운 붓터치의 회화로 파장을 일으켰다. 견고하면서도 자유로운 면의 건축적 조화, 살아있는 질감과 색의 조합을 빛으로 확장하는 작업을 지속해오고 있다. 1981년 버밍엄(Birmingham, England)의 Ikon 갤러리에서 열린 첫 회고전을 시작으로 미국과 유럽, 아시아에 이르기까지, 전세계적으로 활동을 지속하고 있다. 그의 작업은 Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY, US), National Gallery of Art(Washington, D.C.), Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen(Düsseldorf, Germany), Musee National d´Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou(Paris, France) 등 미국과 유럽 전역의 주요 미술관과 공공 기관에 소장되어 있다. 그는 크로이던(Croydon College of Art)에서 수학하던 중 뉴캐슬 대학교(Newvastle University)로 학교를 옮겨 졸업하였다. 이후에 하버드대학교(Harvard University) 대학원에서 Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts 펠로우쉽(fellowship)을 받았다.

Kim Ho Deuk (b.1950, Daegu, South Korea) has been presenting various painterly experiments based on ink wash painting for over 40 years, starting with a solo exhibition at the Gwanhun Museum of Art in 1986. He has held solo exhibitions at venues such as Hakgojae (Seoul, 2019), Mountain Water (Gallery Bundo, Daegu, 2018), ZIP – Garage, BIGO (Paradise ZIP, Daegu, 2017), Just, Suddenly (Kim Jong Young Art Museum, Seoul, 2014). He has received awards including the Kim Swoo Geun Cultural Award in Fine Arts (Kim Swoo Geun Foundation, Seoul, 1993), the Total Grand Prix (Total Museum, Jangheung, 1995), and the Lee Joong Sup Award (Chosun Ilbo, Seoul, 2003). His works are held in the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Samsung Museum of Art, Daejeon Museum of Art, Daegu Art Museum, Kumho Museum of Art, Ilmin Museum of Art, Ho-Am Art Museum, and others.

Kim graduated from the Department of Painting at Seoul National University and received a master's degree in Oriental Painting from the graduate school.

Bae Bien U (b.1950, Yeosu, South Korea) has been engaged in international activities since his first solo exhibition in 1982. In 2006, as an Asian photographer, he became the first to hold a solo exhibition at the Thyssen Bornemisza Museum in Spain, and he was commissioned by the Spanish government to photograph the gardens of the Alhambra Palace, a UNESCO World Heritage site, for two years. Bae held touring exhibitions at the Alhambra Palace and the Deoksugung Palace Museum in Seoul. Additionally, he has held major solo exhibitions at various venues, including the Gwangju City Museum (2015), Musée d'art moderne de Saint-Étienne in France (2015), Château de Chambord in France, and the Wilmotte Foundation (2022, Venice, Italy). In 2016, Bae received the Lee Joong Sup Award and in 2023, he was awarded the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by the French government.

Bae graduated from the Department of Applied Arts and the graduate school at Hongik University's College of Fine Arts.

Suh Yong Sun (b.1951, Seoul, South Korea) has been praised for using a distinctive visual language of dense and constructed planes, as well as challenging and rough textures, to elevate the issues of human existence. Suh has held solo exhibitions such as Suh Yong Sun: My Name is Red (Art Sonje Center, Seoul, 2023), The Story of Magoh: In Search of the Goddess Within Us (Seoul Women's History and Culture Space Yeodamjae, 2021), Suh Yong Sun's Landscape Paintings of Mancheop Mountain (Yeojoo Museum of Art, Yeojoo, 2021), Pain · Symptom · Diagnosis: Drawing the History of Suh Yong Sun (Art Center White Block, Paju, 2019), Expanding Lines, Suh Yong Sun Drawing (Arko Art Center, Seoul, 2016). Suh has been awarded numerous accolades including being selected as the Artist of the Year (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2009) and receiving the Lee Joong Sup Award (Chosun Ilbo, Seoul, 2014). In 2023, Suh is planning to unveil a mural commemorating the 100th anniversary of the "Amtae Farmers' Struggle," a 1920s anti-Japanese movement, at the former Amtae Nonghyup Warehouse located in Shinan.

Suh graduated from the Department of Painting at Seoul National University and received a master's degree in department of Painting from the graduate school.

Sean Scully (b.1945, Dublin, Ireland) challenged the minimalist painting movement of the 1980s in New York with his expressive brushstroke paintings, creating ripples in the art world. His works are characterized by a balance between solid yet free architectural harmony, vibrant textures, and combinations of colors that expand into light. Sean began his artistic journey with his first retrospective at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England in 1981 and has since maintained a global presence, exhibiting across the United States, Europe, and Asia. Sean's works are held in major art museums and public institutions worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY, US), National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (Düsseldorf, Germany), Musee National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris, France), and others.

Sean studied at Croydon College of Art and later transferred to Newcastle University, where he graduated. He also received a fellowship from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University while pursuing his graduate studies there.

배병우(b.1950b, 여수, 한국)는 1982년 첫 개인전 이후로 국제적인 활동을 이어오고 있다. 2006년 아시아 사진작가로는 최초로 스페인 티션보르네미서 미술관(Thyssen Bornemisza Museum)에서 개인전을 열었고 스페인 정부의 의뢰로 세계문화유산인 알함브라궁전의 정원을 2년간 촬영하여 알함브라 궁전과 서울 덕수궁 미술관에서 순회 전시를 진행하기도 하였다. 이 밖에 광주시립미술관(2015), 프랑스 생테티엔 미술관(Musee d'art moderne de saint-etienne, France, 2015), 프랑스 국립재단 샹보르 성(Château de Chambord, France), 빌모트 재단(Wilmotte Foundation, 2022, Venice, Italy) 등에서 대규모 개인전을 열었다. 2016년 이중섭미술상과 2023년 프랑스 정부에서 문화예술공로훈장 슈발리에장을 수여 받았다. 그는 홍익대학교 미술대학 응용미술학과와 동대학원을 졸업하였다.

서용선(b.1951, 서울, 한국)은 밀도 있고 구축적인 평면과 도전적일 정도로 거친 질감의 표현을 통해 인간실존의 문제를 특유의 조형언어로 승화시킨다는 평을 받고 있다. 서용선: 내 이름은 빨강(아트선재, 서울, 2023), 서용선의 마고 이야기, 우리안의 여신을 찾아서(서울여성역사문화공간 여담재, 2021), 만첩산중 서용선 회화(여주미술관, 여주, 2021), 통증 ·징후 ·증세:서용선의 역사 그리기(아트센터화이트블럭, 파주, 2019), 확장하는 선, 서용선 드로잉(아르코미술관, 서울, 2016) 등에서 개인전을 진행하였다. 올해의 작가(국립현대미술관, 과천, 2009)에 선정되고 이중섭미술상(조선일보사, 서울, 2014) 등 다수의 상을 수여받았다. 2023년 가을 신안에 위치한 옛 암태농협창고에서 1920년대 항일운동인 ‘암태도 소작항쟁’ 100주년 벽화를 공개할 예정이다. 그는 서울대학교 미술대학 회화과를 졸업하고 동 대학원 서양화과에서 석사 학위를 받았다.

션 스컬리(Sean Scully, b.1945, Dublin, Ireland)는 1980년대 미국 뉴욕의 미니멀리즘 회화 운동에 반(反)하며 자유로운 붓터치의 회화로 파장을 일으켰다. 견고하면서도 자유로운 면의 건축적 조화, 살아있는 질감과 색의 조합을 빛으로 확장하는 작업을 지속해오고 있다. 1981년 버밍엄(Birmingham, England)의 Ikon 갤러리에서 열린 첫 회고전을 시작으로 미국과 유럽, 아시아에 이르기까지, 전세계적으로 활동을 지속하고 있다. 그의 작업은 Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY, US), National Gallery of Art(Washington, D.C.), Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen(Düsseldorf, Germany), Musee National d´Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou(Paris, France) 등 미국과 유럽 전역의 주요 미술관과 공공 기관에 소장되어 있다. 그는 크로이던(Croydon College of Art)에서 수학하던 중 뉴캐슬 대학교(Newvastle University)로 학교를 옮겨 졸업하였다. 이후에 하버드대학교(Harvard University) 대학원에서 Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts 펠로우쉽(fellowship)을 받았다.

Kim Ho Deuk (b.1950, Daegu, South Korea) has been presenting various painterly experiments based on ink wash painting for over 40 years, starting with a solo exhibition at the Gwanhun Museum of Art in 1986. He has held solo exhibitions at venues such as Hakgojae (Seoul, 2019), Mountain Water (Gallery Bundo, Daegu, 2018), ZIP – Garage, BIGO (Paradise ZIP, Daegu, 2017), Just, Suddenly (Kim Jong Young Art Museum, Seoul, 2014). He has received awards including the Kim Swoo Geun Cultural Award in Fine Arts (Kim Swoo Geun Foundation, Seoul, 1993), the Total Grand Prix (Total Museum, Jangheung, 1995), and the Lee Joong Sup Award (Chosun Ilbo, Seoul, 2003). His works are held in the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Samsung Museum of Art, Daejeon Museum of Art, Daegu Art Museum, Kumho Museum of Art, Ilmin Museum of Art, Ho-Am Art Museum, and others.

Kim graduated from the Department of Painting at Seoul National University and received a master's degree in Oriental Painting from the graduate school.

Bae Bien U (b.1950, Yeosu, South Korea) has been engaged in international activities since his first solo exhibition in 1982. In 2006, as an Asian photographer, he became the first to hold a solo exhibition at the Thyssen Bornemisza Museum in Spain, and he was commissioned by the Spanish government to photograph the gardens of the Alhambra Palace, a UNESCO World Heritage site, for two years. Bae held touring exhibitions at the Alhambra Palace and the Deoksugung Palace Museum in Seoul. Additionally, he has held major solo exhibitions at various venues, including the Gwangju City Museum (2015), Musée d'art moderne de Saint-Étienne in France (2015), Château de Chambord in France, and the Wilmotte Foundation (2022, Venice, Italy). In 2016, Bae received the Lee Joong Sup Award and in 2023, he was awarded the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres by the French government.

Bae graduated from the Department of Applied Arts and the graduate school at Hongik University's College of Fine Arts.

Suh Yong Sun (b.1951, Seoul, South Korea) has been praised for using a distinctive visual language of dense and constructed planes, as well as challenging and rough textures, to elevate the issues of human existence. Suh has held solo exhibitions such as Suh Yong Sun: My Name is Red (Art Sonje Center, Seoul, 2023), The Story of Magoh: In Search of the Goddess Within Us (Seoul Women's History and Culture Space Yeodamjae, 2021), Suh Yong Sun's Landscape Paintings of Mancheop Mountain (Yeojoo Museum of Art, Yeojoo, 2021), Pain · Symptom · Diagnosis: Drawing the History of Suh Yong Sun (Art Center White Block, Paju, 2019), Expanding Lines, Suh Yong Sun Drawing (Arko Art Center, Seoul, 2016). Suh has been awarded numerous accolades including being selected as the Artist of the Year (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, 2009) and receiving the Lee Joong Sup Award (Chosun Ilbo, Seoul, 2014). In 2023, Suh is planning to unveil a mural commemorating the 100th anniversary of the "Amtae Farmers' Struggle," a 1920s anti-Japanese movement, at the former Amtae Nonghyup Warehouse located in Shinan.

Suh graduated from the Department of Painting at Seoul National University and received a master's degree in department of Painting from the graduate school.

Sean Scully (b.1945, Dublin, Ireland) challenged the minimalist painting movement of the 1980s in New York with his expressive brushstroke paintings, creating ripples in the art world. His works are characterized by a balance between solid yet free architectural harmony, vibrant textures, and combinations of colors that expand into light. Sean began his artistic journey with his first retrospective at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England in 1981 and has since maintained a global presence, exhibiting across the United States, Europe, and Asia. Sean's works are held in major art museums and public institutions worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY, US), National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (Düsseldorf, Germany), Musee National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris, France), and others.

Sean studied at Croydon College of Art and later transferred to Newcastle University, where he graduated. He also received a fellowship from the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University while pursuing his graduate studies there.

중용지도 中庸之道 Golden Means

김호득, 배병우, 서용선, 션 스컬리

Bae Bien U, Kim Ho Deuk, Sean Scully, Suh Yong Sun

2023.8.30~10.31

Reservation Only

김호득, 배병우, 서용선, 션 스컬리

Bae Bien U, Kim Ho Deuk, Sean Scully, Suh Yong Sun

2023.8.30~10.31

Reservation Only