SEOUL

Joo Myung Duck

Joo Myung Duck

SEOUL, Installation in Obscura, 2022

한국 사진사의 1세대인 주명덕은 사회적 다큐멘터리작업인 <포토·에세이 홀트씨 고아원>(1966) 전시로 전후한국 사회에서 외면했던 혼혈고아 문제를 처음 세상에 알렸다. 이 전시의 자료를 정리하여 출판된 것이 『섞여진 이름들』(1969)이다. <서울>은 1969년 주명덕의 첫 책을 비롯하여 신간 『SEOUL』(옵스큐라, 2022)까지 작품집 40여 권과 글을 모아 그의 작품 세계전반을 살펴볼 수 있는 아카이브 전시이다.

‘서울’은 주명덕에게 평생의 일기와도 같은 소재이다. 한국의 온 지역과 공간, 자연, 여러 인물을 통해 작품세계를 펼쳐 나간 주명덕의 방대한 작업들이 있지만, ‘서울’ 작업은 60여 년간의 작업 흐름을 그대로 축약해 놓았다 해도 과언이 아니다. 20대 초기 매그넘, 유진 스미스, 윌리엄 클라인 등에 영향을 받은 습작에서 시작하여 1960~70년대 자신만의 언어로 사회적 다큐멘터리를 열어 나갔다. 2000년대 도시정경과 추상적 미학을 담는 장년기 작업에 이르기까지 그에게 서울은 끝없는 피사체였다. 이번 전시에서 선보이는 『SEOUL』은 주명덕 작업은 서울의 기록과 그의 미학적 흐름을 담은 작품집이다.

옵스큐라의 기획전시 <서울>에서는 구하기 힘든 1970~80년대 출판된 주명덕의 책을 직접 볼 수 있다. 『명시의고향』(성문각,1971), 『정읍 김씨집』(열화당, 1976), 『韓国の空間 한국의 공간』(구용당, 일본, 1985) 등이다. 그 중 『韓国の空間 한국의 공간』은 월간중앙에 재직하며 발표했던 ‘한국의 이방, 한국의 가족, 은발의 한국인, 명시의 고향, 한국의 메타포, 국토의 서정기행’, 총 6개의 시리즈를 담은 책으로 1970년대 시대성을 담아 한국의 뿌리를 국제적으로 선보인 주명덕의 작업을 한눈에 볼 수 있다.

주명덕 작품론의 이해를 돕기 위해 그의 작업노트와 인터뷰 일부를 정리한 아카이브를 볼 수 있다. 1969년 주명덕의 첫 책에 남겼던 작가로서의 굳은 다짐을 적어 놓은 노트, 2000년 작업실에서 소탈하게 밝힌 작품 변화 과정의 인터뷰, 70대 작가로서의 감사와 소망 등 다양한 방식으로 관람객을 맞이한다. 전시는 오는 5월 30일까지 옵스큐라에서 열린다.◼️옵스큐라 오진령, 박우진

Joo Myung Duck is among the first generation of Korean photographers, whose exhibition Photo and Essay Holt's Orphanage (1966) revealed to the world for the first time the issue of mixed-race orphans from the Korean War, which was neglected afterwards by Korean society. The materials for this exhibition were compiled and published in Mixed Names (1969). Seoul is an archive exhibition that showcases a total of forty works and writings that were collected from various sources, spanning across Joo’s first book in 1969 and his new publication SEOUL, published by Obscura in 2022.

Seoul is like a lifelong diary for him. On one hand, Joo has an enormous body of work that takes as his subject matters various regions, landscapes, built spaces, and individuals throughout Korea. On the other hand, it is no exaggeration that his works that depict Seoul are like a condensed version of his body of work that has been built over the span of more than 60 years. In his early 20s, he took influence from Magnum, Eugene Smith, and William Klein, and began making social documentaries in his own language in the 1960s and 1970s. For him, Seoul was a diary-like subject, from the 2000s to his work in adulthood with urban scenes and abstract aesthetics. SEOUL, which will be presented in this exhibition, is also a collection of Joo’s works that have recorded Seoul's records through his aesthetic eyes.

Visitors to this special exhibition at Obscura Gallery will find Joo’s books that have been published in the 1970s and 1980s and are difficult to access, such as Hometown of Myeongsi (Seoul: Seongmungak, 1971), Kim's House of Jeongeup (Paju, South Korea: Yeolhwadang, 1976), and Korean Space(Tokyo: Kyuryudo 1985). Among them, Korean Space is noteworthy for the following six series of his work: Korean Immortals, Korean Families,Silver-haired Koreans, Myungeun's Hometown, Korean Metaphor, and Land's Lyric Journey," all of which present a vivid historical portrait of Korea in the 1970s.

The special exhibition at Obscura offers various archival materials for better understanding of his work. These include Joo’s personal notes from 1969, interviews in his studio in 2000, and messages of gratitude and wishes that he expressed as an artist in his 70s. The exhibition opens through May 30 at Obscura Gallery◼Obscura Oh and Park

‘서울’은 주명덕에게 평생의 일기와도 같은 소재이다. 한국의 온 지역과 공간, 자연, 여러 인물을 통해 작품세계를 펼쳐 나간 주명덕의 방대한 작업들이 있지만, ‘서울’ 작업은 60여 년간의 작업 흐름을 그대로 축약해 놓았다 해도 과언이 아니다. 20대 초기 매그넘, 유진 스미스, 윌리엄 클라인 등에 영향을 받은 습작에서 시작하여 1960~70년대 자신만의 언어로 사회적 다큐멘터리를 열어 나갔다. 2000년대 도시정경과 추상적 미학을 담는 장년기 작업에 이르기까지 그에게 서울은 끝없는 피사체였다. 이번 전시에서 선보이는 『SEOUL』은 주명덕 작업은 서울의 기록과 그의 미학적 흐름을 담은 작품집이다.

옵스큐라의 기획전시 <서울>에서는 구하기 힘든 1970~80년대 출판된 주명덕의 책을 직접 볼 수 있다. 『명시의고향』(성문각,1971), 『정읍 김씨집』(열화당, 1976), 『韓国の空間 한국의 공간』(구용당, 일본, 1985) 등이다. 그 중 『韓国の空間 한국의 공간』은 월간중앙에 재직하며 발표했던 ‘한국의 이방, 한국의 가족, 은발의 한국인, 명시의 고향, 한국의 메타포, 국토의 서정기행’, 총 6개의 시리즈를 담은 책으로 1970년대 시대성을 담아 한국의 뿌리를 국제적으로 선보인 주명덕의 작업을 한눈에 볼 수 있다.

주명덕 작품론의 이해를 돕기 위해 그의 작업노트와 인터뷰 일부를 정리한 아카이브를 볼 수 있다. 1969년 주명덕의 첫 책에 남겼던 작가로서의 굳은 다짐을 적어 놓은 노트, 2000년 작업실에서 소탈하게 밝힌 작품 변화 과정의 인터뷰, 70대 작가로서의 감사와 소망 등 다양한 방식으로 관람객을 맞이한다. 전시는 오는 5월 30일까지 옵스큐라에서 열린다.◼️옵스큐라 오진령, 박우진

Joo Myung Duck is among the first generation of Korean photographers, whose exhibition Photo and Essay Holt's Orphanage (1966) revealed to the world for the first time the issue of mixed-race orphans from the Korean War, which was neglected afterwards by Korean society. The materials for this exhibition were compiled and published in Mixed Names (1969). Seoul is an archive exhibition that showcases a total of forty works and writings that were collected from various sources, spanning across Joo’s first book in 1969 and his new publication SEOUL, published by Obscura in 2022.

Seoul is like a lifelong diary for him. On one hand, Joo has an enormous body of work that takes as his subject matters various regions, landscapes, built spaces, and individuals throughout Korea. On the other hand, it is no exaggeration that his works that depict Seoul are like a condensed version of his body of work that has been built over the span of more than 60 years. In his early 20s, he took influence from Magnum, Eugene Smith, and William Klein, and began making social documentaries in his own language in the 1960s and 1970s. For him, Seoul was a diary-like subject, from the 2000s to his work in adulthood with urban scenes and abstract aesthetics. SEOUL, which will be presented in this exhibition, is also a collection of Joo’s works that have recorded Seoul's records through his aesthetic eyes.

Visitors to this special exhibition at Obscura Gallery will find Joo’s books that have been published in the 1970s and 1980s and are difficult to access, such as Hometown of Myeongsi (Seoul: Seongmungak, 1971), Kim's House of Jeongeup (Paju, South Korea: Yeolhwadang, 1976), and Korean Space(Tokyo: Kyuryudo 1985). Among them, Korean Space is noteworthy for the following six series of his work: Korean Immortals, Korean Families,Silver-haired Koreans, Myungeun's Hometown, Korean Metaphor, and Land's Lyric Journey," all of which present a vivid historical portrait of Korea in the 1970s.

The special exhibition at Obscura offers various archival materials for better understanding of his work. These include Joo’s personal notes from 1969, interviews in his studio in 2000, and messages of gratitude and wishes that he expressed as an artist in his 70s. The exhibition opens through May 30 at Obscura Gallery◼Obscura Oh and Park

해석자의 심미안: 주명덕의 『서울』

1.

『서울』은 주명덕이 반세기 동안 도시 서울을 기록한 작업을 정리해서 보여준다. 1960-70년대의 작업을 모은 1부와 2000년대 이후의 작업을 정리한 2부는 한눈에 보아도 확연히 구분되는 차별성을 갖는다. 60-70년대는 주로 인간에, 2000년대 이후는 주로 도시 공간에 관심이 집중되어 있으며, 카메라 워크와 작업 형식에도 큰 차이가 있다.

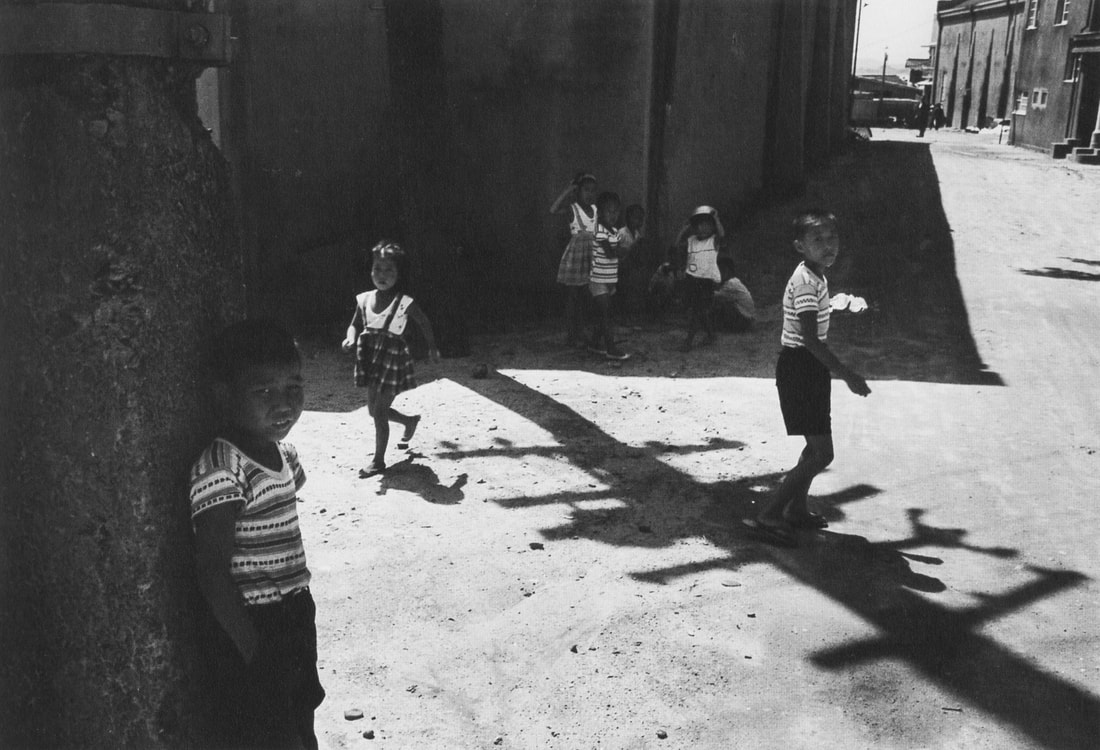

1960-70년대의 서울은 한국전쟁 이후 폐허가 된 도시의 복구와 급속한 개발이 동시에 진행되던 시기다. 따라서 전쟁의 상흔과 전통의 흔적, 개발의 생채기가 도시 곳곳에 뒤죽박죽 섞여 있다. 실상 1960년대는 주명덕의 작업여정에서 소위 ‘습작의 시기’에 가깝다. 작가의 대표작으로 평가받는 <홀트씨고아원>전(1966)과 비슷한 시기의 작업이지만 명료한 문제의식과 완성도 높은 형식을 취한 이 포토에세이와 달리 60년대의 서울작업에서 작가는 자신이 배워 온 다양한 사진의 문법들을 적용, 실험하고 있다. 여기에는 1950년대에 전쟁 직후의 ‘생활상’을 진솔하게 담아내고자 했던 생활주의사진이나 리얼리즘사진의 유산도 미미하나 남아있고, 서양의 사진화보 잡지를 통해 광범위하게 배포되던 포토저널리즘이나 다큐멘터리 사진의 영향도 보인다. 나아가 60년대 <현대사진연구회>의 일원으로 활동하면서 ‘학습’했던 조형주의 사진의 형식적 요소도 섞여있다. 구도와 빛의 처리, 기하학적 형태를 찾아내어 ‘조형성’을 강조하기 위한 의식적인 관점의 선택 등이 그 예다. 말하자면 60년대의 서울 작업에서 주명덕은 자신이 배웠던 대부분의 사진 형식을 자유롭게 시도하고 있다. 그만큼 다양한 시각이 혼재돼 있다는 뜻이다.

1970년대로 진입하면서 주명덕은 기획 취재 형식으로 분명한 주제를 설정하여 서울에 접근한다. 1970년대의 서울 작업에는 『월간중앙』에 발표했던 <한국의 가족> 연작이 주로 포함돼 있다. 이 연작의 주제는 60년대부터 진행된 산업화와 개발로 빠르게 해체되어 가는 한국의 가족제도다. 전통적인 대가족제는 농촌사회의 극히 일부에만 남게 되고 급속한 도시화 과정에서 핵가족제가 보편적인 가족형태로 자리 잡게 됐다. 또한 무분별한 도시계획과 신도시 개발의 와중에서 터를 잃고 쫓겨나는 가족도 생겨났다. 이 급격한 변화에도 불구하고 서울의 가족들은 묵묵히 희망을 갖고 일상을 살아간다. 주명덕이 기록한 1960-70년대 서울의 모습은 전쟁과 개발, 산업화라는 미증유의 격변기를 살아가는 사람들의 충실한 자화상이다.

2.

2000년대 이후의 서울에 대한 작업은 1960년대 이후 줄곧 그의 사진 스타일을 지배해 왔던 ‘전통적인’ 다큐멘터리 방식과 차별성을 갖는다. 초기 작업에 해당하는 <섞여진 이름들>에서부터 <한국의 가족>, <한국의 이방>, <한국의 공간> 등에서는 절제 있고 엄격한 중립적 시각이 사진 전체를 지배하고 있었다. 이는 그가 일찍이 사진을 ‘사실과 기록’의 관점에서 수용했기 때문이다. 그리고 이런 시각은 대부분의 작업에서 일관되게 지속되고 있다. 그러나 이 태도가 그의 작업을 ‘시각적 보고서’의 차원에만 머무르게 하지는 않는다. ‘주관적’ 기록이기 때문이다. 그리고 이 주관적 기록의 바탕에는 그만의 고유한 심미적 시선이 깔려있다.

2000년대의 도시 사진이 기존 작업과 갖는 눈에 띄는 차이는 기록의 관점에서 진행했던 기존 작업의 스타일에서 벗어나 있다는 점에 있다. 우선 역동적인 촬영 시점과 앵글의 선택이 눈에 띈다. 나아가 초점이 맞지 않거나 흔들린 이미지도 많아 이 작업에서 정보가치는 크게 중요치 않아 보인다. 또한 의도적인 중첩과 반영 효과를 자주 활용하고 있어 촬영 목표에 집중하고 있지 않다는 인상마저 풍긴다. 서울이라는 도시를 효율적으로, 즉 객관적 정보를 담고 있는 사진으로 기록할 의도는 별로 없었던 것 같다. 왜 이런 방식을 취한 것일까? 도시 사진을 모아 2008년 대림미술관에서 열린 전시 제목은 도시정경(都市情景)이다. 정경(情景), 요컨대 도시가 불러일으키는 정서가 중요하다는 뜻이다. 마음의 풍경이라고도 할 수 있겠다. 말하자면 도시가 자신에게 불러일으키는 감흥을 사진으로 옮겨낸 셈이다.

실상 주명덕의 기존 작업에는 역사가나 사회학자의 ‘탐구적’ 태도가 깔려있었다. <섞여진 이름들>에서는 한국전쟁에 관한 거대담론이 미처 보지 못했던 혼혈 고아 문제를 예리하게 들추어냈고, <한국의 가족>에서는 근대화라는 문명사적 전환기에 한국의 가족제도가 어떻게 변화하고 있는지를 유형별로 정리했다. <한국의 공간>은 급격히 진행된 ‘서양식’ 근대화 과정에서도 굳건히 남아있는 우리 공간의 전통적 아름다움을 보여주는 데 심혈을 기울였다. 이 모든 작업에서 그는 절제와 배려의 자세를 유지했다. 인간에 대해서는 휴머니즘과 존중의 태도를, 공간에 대해서는 과장과 수사를 멀리하고 대상에 충실하고자 했다. 그것으로 충분했기 때문이다. 그것이 주명덕의 심미적 시선 바탕에 깔려있는 윤리적 태도이기도 하다.

그런데 이제 도시정경에 와서 그런 태도에 변화가 생겼다. 이 변화는 시기적으로는 1990년대에 와서 구체화된 <잃어버린 풍경(Lost Landscape)>에서부터 이미 시작됐던 것으로 보인다. 한국의 자연을 보여주는 이 작업의 시각적 특징은 사진 전체가 온통 어둡고 검은 톤으로 덮여 있다는 점이다. 이른바 ‘검은 풍경’이다. 이 작업에서 본래의 나무와 풀, 산이 갖고 있는 형태는 어둠에 묻혀 간신히 모습을 드러낼 뿐이다. 시각적 특성만을 놓고 본다면 서양 모더니즘 회화에서의 모노크롬이나 한국의 단색화와 비견될만하다. 이런 특징은 1970-80년대의 작업과 비교할 때 형식주의의 차원에서 눈에 띄는 큰 변화다. 주명덕은 이 작업의 바탕에 깔려있는 의도를 다음과 같이 밝힌 바 있다. “조국이 갖고 있던 아름다운 자연환경과 전통, 사람들이 지니고 있는 소박한 마음을 내 사진을 통하여 이 모든 것을 잃어버린 세대들에게 남겨보려는 작업을 계속해 왔다”는 것이다. 말하자면 ‘기록’에서 출발했으나 그 의도는 조국 산천의 아름다움과 사람들의 소박한 마음을 사진으로 표현하는 데 있다. 그것을 ‘잃어버려’ 보지 못하는 세대에게 자신의 심미적 시선을 통해 그 아름다움을 보여주고 싶었다고 할 수 있겠다. ‘검은 풍경’은 결국 그의 주관적 시선, 심미적 시선이 드러나는 모습이다. 여기서 나무의 형태나 톤이 본래의 그것과 얼마나 일치하느냐는 중요하지 않다. 자신이 그렇게 본다는 사실만으로 족하기 때문이다. 말하자면 ‘검은 풍경’ 역시 정경, 즉 자연이 그에게 불러일으키는 정서를 반영한다.

3.

그렇다면 도시는 그에게 어떤 정서를 불러일으켰을까? 첫째, 역동성과 긴장감이다. 역동성은 어떻게 표현될까? 통상적인 눈높이 시점을 대신하여 로우 앵글로 쳐다보는 방법이 있다. 그리고 실제 고층빌딩으로 가득 찬 서울에서 건물의 모습 전체를 보려면 올려다보는 수밖에 없다. 그렇게 고개를 쳐들고 빌딩을 보면 하늘이 함께 보이고, 인공구조물 옆으로 배치된 자연을 가장한 거대한 가로수도 병치 상태로 시야에 들어온다. 그러나 그 모습은 자연과 인공이 서로 노려보는 형태로 적대적 긴장감을 유지하고 있다.

둘째, 반영과 중첩. 도시정경에서 가장 자주 등장하는 요소로 작가의 시선을 유달리 잡아끈 모습이다. 실상 현대 도시 건축에서 유리가 건축자재로 활용되는 비중은 매우 높다. 빽빽이 가득 찬 폐쇄적인 건축물의 공간 구조에서 막힌 시야를 열어주는 방법은 유리의 투명성에 의존하는 것밖에 없기 때문이다. 그리고 유리의 투명성은 현대미술에서, 예컨대 미래파 작가들에게는 가장 전형적인 현대적 시각경험을 제공하는 수단이었다. 실제 도시 바깥으로 나가면 인간의 거주 공간에서 시야가 막힐 일은 거의 없다. 그런데 유리는 투명성만 가진 물질이 아니다. 보는 각도에 따라 맞은 편 이미지의 반영도 있고 굴절도 있다. 따라서 유리는 투명한 건너편 이미지와 보는 자의 편에서 유리 표면에 반사된 이미지의 중첩 효과를 만들어낸다. 이 효과는 비현실적이기도 하고, 기이하거나 몽환적이기도 하며, 놀랄 만큼 아름답거나 괴기스럽기도 하다. 어쨌든 일상에서 만나는 평범한 시각적 경험과 크게 다르다. 그리고 그 효과는 보는 자의 의도와 무관하게 우연히 찾아온다. 그럼에도 불구하고 그 우연을 카메라로 포착하는 것은 순전히 작가의 의지에 달려있다.

반영과 중첩을 통해 주명덕의 시선을 잡아끈 이미지는 대부분 광고 포스터에 등장하는 서양의 모델들이다. 그리고 그 이미지는 대체로 패션, 악세사리, 화장품 등의 광고 모델로 추정된다. 모델의 포즈와 표정, 메이크업 등을 <도시정경>의 작가가 선택한 것이 아니기에 그 여성들의 모습은 일반적인 광고 전략의 프로토타입을 따르고 있다. 이른바 스테레오타입으로서의 아름답고 우아한 모습의 여성들인 셈이다. 이 ‘매혹적인’ 여성 모델의 이미지가 도시에 넘쳐난다는 것은 그 이미지가 도시 군중의 정서에 부합한다는 뜻이기도 하다. 60년대 이후 한국이 걸어 온 ‘서양식’ 근대화 과정을 꾸준히 기록해 온 작가의 눈에 이 모습은 어찌 보면 당연할 수 있다. 그리고 이는 자본주의의 고도화에 따른 필연적 결과이기도 하다. 이렇게 서양의 자본주의가 ‘제작한’ 여성 이미지는 서울이라는 실제 도시와 중첩을 통해 섞여 들어가는 모습을 보여준다. 그런 점에서 <도시정경>은 형식적 변화에도 불구하고 과거 작업의 연장선상에 있다.

셋째, 자연과 문화의 혼합. 여기에 해당하는 이미지는 도시의 담벼락과 바닥에 덮여있는 페인트칠이 세월의 흐름에 따라 훼손되면서 만들어 낸 추상적 형태를 보여준다. 잿빛 콘크리트를 덮기 위한 페인트칠이나 복잡한 도시에서 효율적인 의사소통을 위해 곳곳에 새겨 놓은 각종 기호들은 풍화와 침식이 진행되면서 예기치 않았던 형태로 변형된다. 문화적 행위가 자연의 위력과 섞이면서 만들어낸 뜻밖의 이미지인 셈이다. 그리고 그 형태는 대체로 추상 이미지로 귀착한다. 그런데 작가는 왜 이 ‘하찮은’ 벗겨진 페인트, 혹은 ‘남겨진’ 페인트의 형상에 주목했을까?

아마도 도시에서 가장 쉽게 볼 수 있는 이미지이기 때문일 것이다. 도시는 수많은 군중들 간 소통의 효율성을 위해, 도시 보존과 재생을 위해, 콘크리트의 잿빛을 감추기 위해 끊임없이 페인트를 부어댄다. 그리고 그 행위는 구체적 형상을 목표로 삼지 않기에 ‘대충’ 이루어진다. 자연의 훼손도 같은 방향으로 진행된다. 지우고 삭제할 요소를 가리지 않는다는 뜻이다. 그렇게 ‘변형된’ 형상, 결국 새로 ‘생성된’ 형상은 어떠한 구체성도 띄지 않는다. 추상 이미지로 남게 되는 것이다. 결국 도시는 이렇게 탄생한 무수한 추상 이미지로 뒤덮여 있다. 도시가 구축과 훼손, 재생의 메커니즘을 끊임없이 반복하는 한 추상 이미지는 계속해서 변형과 생성을 거듭해나간다.

4.

다른 한편으로 작가가 이 추상 이미지에 관심을 갖게 된 데는 ‘새로운’ 작업, 즉 기존의 규범에 얽매이지 않고 자유롭게 사진작업을 해보고자 하는 욕망이 바탕에 깔려있는 것 같다. 이 문제는 작가의 기나긴 사진작업의 여정과 한국 사진의 역사적 맥락을 함께 고려해야 한다. 주명덕의 초기 작업이 시작되던 1960년대는 1950년대 이후 한국사진의 ‘주류’로 자리 잡은 생활주의 사진의 영향이 여전히 남아있던 시기다. 생활주의는 현실의 삶을 진솔하게 기록하자는 리얼리즘 정신에 입각하여 전개된 사진운동이다. 주명덕이 ‘사실성’, ‘기록성’을 사진의 본질적 미학으로 수용하게 된 데는 이런 맥락이 깔려있다. 이 시기 한국사진에 리얼리즘만 있었던 것은 물론 아니다. 소위 모더니즘 사진을 지향하는 다른 시도들도 존재했으나 성과는 미약했다. 생활주의로 대표되는 리얼리즘 사진도 한계에 봉착해 있었다. 생활주의는 해방과 한국전쟁을 거치면서 분명 사진가들에게 새로운 미학의 가능성을 보여주었다. 특히 해방 이전의 이른바 ‘살롱사진’ 전통에 익숙해 있던 사진가들에게 한국전쟁의 참상은 사진이 리얼리즘 정신을 망각해서는 안 된다는 각성을 불러일으켰던 측면이 있다. 그러나 생활주의는 공모전이라는 제도의 한계를 넘지 못했고, 따라서 형식의 정형성에 갇히거나 편협한 주제에 매몰되어 쇠락의 길을 걷고 있었다. 주명덕이 <섞여진 이름들>에서 보여주었던 포토에세이 형식이나 이후 잡지사진에서 시도했던 기획 취재 형식의 다큐멘터리 작업은 이처럼 생활주의와 리얼리즘 사진이 봉착했던 한계를 넘어 기록의 언어를 폭넓게 확장시킨 뛰어난 성과로 평가받는다. 그리고 그 과정에서 작가의 ‘심미적 기록’은 하나의 스타일로 굳어갔다.

‘사실성’과 ‘기록성’에 대해 초기부터 작가가 가졌던 신념은 결국 사진은 필연적으로 구체적 대상과 분리될 수 없다는 사진의 속성을 수용한 데서 비롯된 것이다. 이는 사진의 ‘예술성’은 바로 그 속성에 있다는 사진 고유의 미학에 대한 인정으로 귀결됐다. 그리고 바로 이 점이 생활주의와 리얼리즘을 거쳐 오랫동안 한국사진의 규범으로 작용해왔다. 그런데 이 규범에 따르면 사진은 구체적 대상과 분리될 수 없기에 사진가는 형상의 ‘제작’에 개입할 수 없다. 현대미술이 형태의 추상을 다양한 방식으로 탐구하는 동안 사진은 현실에 존재하는 구체적 형상만을 다룰 수밖에 없었다. 그렇다면 ‘기록’에 의존해서 사진의 추상을 얻어내는 것은 불가능한가? 실상 <잃어버린 풍경>의 모노크롬에 가까운 ‘검은 풍경’도 일종의 추상이다. 나무와 풀의 구체적 형상이 검은 톤에 묻혀 간신히 모습을 드러내는 이 작업에서 추상을 향한 시도가 시작되었다고 할 수 있다. 그러나 ‘검은 풍경’을 온전한 추상으로 보기는 어렵다. 어찌됐든 나뭇잎이나 나뭇가지와 같은 구체적 형상들이 남아있기 때문이다. 말하자면 화면에서 사물을 몰아내지 않는 한 추상은 구현되지 않는다.

<Abstract> 연작에서 주명덕은 본격적으로 추상의 문제와 대면한다. 이 작업을 통해 작가는 ‘기록’의 방법론을 포기하지 않고도 추상을 얻어낼 수 있는 가능성을 본다. 방법은 의외로 간단하다. 담장이나 도로 바닥에 묻어있는 페인트 자국에 가까이 다가가면 쉽게 추상이 나온다. 하나의 사물이 다른 사물이나 주변 배경으로부터 분리되는 순간 자신의 고유한 구체적 형상은 힘을 잃게 되는 것이다. 따라서 <Abstract>가 보여주는 각각의 이미지가 어떤 사물인지 알 수 없다. 요컨대 무엇을 찍었는지, 어디서 찍혔는지, 본래의 온전한 형태는 어떠했는지 알 수 없다. 그 이미지들은 때로 추상표현주의 회화에 자주 등장하는 그리드 형태로 나타나기도 하고, 잭슨 폴록의 드리핑 기법을 활용하여 물감을 뿌려놓은 올오버(All over) 페인팅처럼 보이기도 한다. 그 외에도 현대 추상미술에서 찾아볼 수 있는 다양한 붓질의 형태들이 있다. 그런데 <Abstract>의 추상 이미지는 작가가 직접 그리거나 제작한 것이 아니라 자연과 인공의 ‘협업’을 통해 저절로 형성된 것이다. 작가는 그 이미지를 ‘단지’ 포획했을 따름이다. 어떤 포획인가?

일상의 시각으로 도시의 담장이나 길바닥을 볼 때 <Abstract>의 이미지처럼 추상화된 형태가 눈에 들어오지는 않는다. 인간의 눈은 우선 전체를 보기 때문이다. 그리고 그 전체의 일부에 관심을 갖게 되면서 부분으로서의 사물을 본다. 이렇게 지각된 사물은 구체적 형태를 지니게 마련이다. 추상적 형태가 지각되는 경우는 매우 드물다. 따라서 작가는 <Abstract> 작업의 추상 이미지를 관심을 갖고 찾아다녔다고 할 수 있다. 여기에는 전체에서 부분을 떼어내서 보는 면밀한 관찰과 주의 깊은 시선이 요구된다. 나아가 카메라라는 기계장치의 강제성에 부합하여 그 부분을 ‘어떻게’ 떼어낼 지도 결정해야 한다. 면의 분할과 비례도 고려해야 하고 산만하게 흩어져 있는 점과 얼룩을 어디서부터 어디까지 화면에 담아낼 지도 결정해야 한다. 결국 <Abstract>에서의 포획은 추상 화가들이 화면을 구성하는 방법과 크게 다르지 않다. 물론 차이는 있다. 사진에서 성공적인 포획이 이루어지려면 이미 주어진 전체 이미지의 결정 구조에 작가의 시각을 개입해야 하는 난제를 해결해야 한다. 적당한 타협이 필요한 것이다. 전체를 변형시킬 수는 없기에 효과적인 추상의 효과를 얻어내기 위해서는 프레임 구성에 면밀한 주의와 고도의 판단이 요구된다. <Abstract>는 그런 종합적 판단과 심미안의 합작품이다.

<도시정경>과 <Abstract>는 주명덕의 전체 작업 여정을 놓고 볼 때 새로운 시도에 해당한다. 초기 작업에서부터 줄곧 ‘기록’의 관점을 유지해 왔기 때문이다. 도시 사진에 나타나는 파격은 그런 점에서 변화를 상징한다. <Abstract> 작업도 그렇다. 그의 관심은 더 이상 기록의 구체성에 있지 않다. 그러나 이런 변화가 이전 작업들과의 단절을 뜻하지는 않는다. 작가는 도시를 다시 보고자 했을 뿐이다. 분명 1960-70년대의 서울과 2000년대의 서울은 다르다. 말하자면 그는 서울을 이전에 비해 훨씬 역동적이고 변화무쌍한 도시로 해석했을 따름이다. 즉 2000년대의 도시 작업에 나타나는 ‘파격’은 자연스런 결과다. 그런 점에서 주명덕의 도시는 ‘기록자’의 시각에 ‘해석자’의 시각이 맞물려 나온 작업이라 할 수 있겠다. ◼️박평종 (미학, 사진비평)

Interpreter’s Eye for Beauty: Seoul of Joo Myung Duck

1.

Seoul is a summary presenting the works of Joo Myung Duck that documents the city of Seoul for half a century. Part 1, which is a collection of works from the 1960s and 1970s clearly differs from Part 2, which is a collection of works from the 2000s onwards. In the 1960s and 1970s, the artist’s attention was mainly focused on humans. On the other hand, after the 2000s, his primary attention was paid to urban spaces. We can also find a big difference in camera work and the work format.

Seoul in the 1960s and 1970s was undergoing a period of rapid development and restoration of the ruined situation after the Korean War. Therefore, the scars of war, traces of tradition, and side effects of development are mingled at every corner of the city. In fact, the 1960s was rather considered the so-called “study period” in the art journey of Joo Myung Duck. Unlike the photo essay from a period similar to that of Harry Holt Memorial Orphanage (1966, Jung-ang Gongbo-gwan, Seoul), which is evaluated as the artist's representative work, yet with a clear critical mind and high degree of completion, the artist applies and try a variety of grammars of photography, in his works of Seoul of the 1960s. In the works of the 1960, we can perceive the slightly remained legacy of photography focused on everyday life and realism photography, which the artist tried to capture “the way of life” right after the war in the 1950s. Moreover, we can also discover the influence of photojournalism and documentary photography, which used to be widely distributed through western photo pictorial magazines. Furthermore, we can also see the presence of the formal elements of formative based on the composition photography, which the artist used to “acquired” while playing a role as a member of the Modern Photography Society in the 1960s. For instance, they include the conscious choice of perspective to emphasize “formative composition” by finding composition, treatment of light, and geometrical forms. In other words, in his Seoul-themed works from the 1960s, Joo is trying most of the photographic forms he had acquired in an uninhibited manner. It means that multifarious perspectives are mixed in the works.

From the 1970s, Joo starts to approach Seoul by establishing a clear theme in the form of planned coverage. The main works on Seoul in the 1970s included the series of Korean Family published in Monthly JoongAng. The theme of this serial work is based on the Korean family system, which undergoes rapid dismantlement due to industrialization and development since the 1960s. The traditional large family system remains only in a small part of rural areas, while the nuclear family system has been established as a universal family form during the process of quick urbanization. In addition, in the middle of reckless urban planning and new town development, some families were forced to leave their homes. Despite these drastic changes, families in Seoul lead their daily lives silently not losing hope. The images of Seoul in the 1960s and 1970s documented by him are self-portraits that faithfully show how people were living in the unprecedented tempestuous times of war, development, and industrialization.

2.

Joo Myung Duck‘s works on Seoul after the 2000s are different from the “traditional” documentary method that has been predominant in his photography style since the 1960s. In his early work The Mixed Names(Seoul;Seongmungak, 1966), Korean Family, Strangers, and Korean Space, the whole photos were chiefly in line with a moderate and strict neutral perspective. This is because the artist accepted photography from the perspective of “facts and records” from an early stage. This perspective has been maintained with consistency in most of his works. However, this attitude does not limit his works to the level of a mere “visual report.” It is because his works are “subjective” records. In addition, the basis of subjective records consists in the unique aesthetic perspective of his own.

The noticeable difference between urban photography from the 2000s and previous works can be found from the fact that it is distant from the style of previous works in terms of records. Above all, what stands out most is the choice of dynamic point of shooting and angle. In addition, since there are plenty of images that are out of focus or had been shaken, the value of information in this work seems to be of little importance. Moreover, the artist frequently uses the intentional overlapping and reflection effects, so the images even give us the impression that the artist is not concentrating on the goal of shooting. It seems that the artist did not have particular intention to record the city of Seoul in an efficient manner, in other words, as photos containing objective information. Then what would made the artist take this method? The exhibition of urban photos held at Daelim Museum in 2008 is entitled Urban Landscape. When it comes to a landscape, it means that emotion evoked by the city is important. It can also be interpreted as a landscape of the mind. In other words, the inspiration that the city arouses in the artist was transferred to the photos.

In fact, Joo Myung Duck's previous works were based on “inquiring” attitude of a historian or sociologist. The Mixed Names keenly revealed the issues of biracial orphans that the metadiscourse about the Korean War failed to discover. On the other hand, Korean Family is a collection arranged by type how the Korean family system is undergoing changes during the transitional period of civilization called modernization. Korean Space focused on how to show our country’s traditional beauty of space, which preserved the firm posture even in the rapid process of “Foregin style”modernization. In all of these works, he maintained an attitude of moderation and consideration. Regarding to humans, he tried to display humanism and respect. At the same time, in relation to space, he made an effort to be faithful to the object while avoiding exaggeration and rhetoric. It is because that was simply enough. This is also the ethical attitude underlying his aesthetic perspective.

However, when dealing with Urban Landscapes, this attitude has changed. It seems that this change has already started with Lost Landscape, which had shaped in the 1990s. The visual characteristics of this work showing the nature of Korea consist in the fact that the entire photo is covered in dark and black tones. We call this the “Black Landscape”. In this work, the original forms of trees, grass, and mountains are surrounded by darkness with slightly visible aspects. From the perspective of visual characteristics alone, it is comparable to the monochrome in foreignmodernist painting or Dansaekhwa[1]. Such characteristics are considered a evident change in terms of formalism compared to the works of the 1970s and 1980s. Joo Myung Duck once expressed his intention underlying this work as follows: “Through my photos, I have been constantly carrying out works in order to leave the beautiful natural environment, traditions of my motherland, as well as the simple and pure heart of our people to the generations who had lost all of these. In other words, it started with “records,” but it intends to express the beauty of mountains and streams of the motherland and the simple and pure heart of the nation through photography. It can be interpreted that the artist wished to show the beauty through his aesthetic perspective to the generations that failed to see by “having lost” them. The Black Landscape is, in the end, the aspect manifesting his subjective and aesthetic perspective. It does not really matter how precisely the shape or tones of the tree correspond to its original facet. It is because it is enough that he himself sees it that way. At the same time, the Black Landscape also reflects the emotional landscape, in other words, the emotion that nature evokes in him.

3.

Then what kind of emotions would the city have evoked in Joo. First, they can be dynamics and tension. How can dynamics be expressed? There is a way of looking at a low angle instead of the usual eye-level viewpoint. To see the entire facet of buildings in Seoul full of skyscrapers, all we can do is to look up to see them. If we look at the building raising our head, we can see not only the sky as well, but also a huge street trees disguising as nature placed next to artificial structures in a juxtaposed state. However, it maintains somewhat hostile tension in the form of which nature stares at artificiality.

Second, the emotions lie in reflection and overlapping. Such elements appear most frequently in the Urban Landscape, and they particularly attract the artist's attention. In fact, glass makes up a large proportion as a building material in modern urban architecture. It is because the only way to open the blocked view in the spatial structure of a closed building that is tightly packed is by depending on the transparency of glass. In addition, for futurist artists, the transparency of glass used to be a means of providing modern visual experience as the most typical pattern in contemporary art. If fact, if we go outside the city, our visibility is hardly blocked in the residence spaces. However, glass is not just a transparent material. Depending on the angle from where we see, there is reflection or refraction of the opposite image. Therefore, glass creates an overlapping effect of the transparent image on the other side in addition to the image reflected on the surface of the glass on the side of the viewer. This effect can be unrealistic, strange, dreamlike, strikingly beautiful or grotesque. In any case, the effect is considerably different from the visual experience we usually encounter in our daily life. In addition, the effect takes place by chance irrespective of the viewer's intentions. Despite this, whether the artist captures this coincidence with the camera or not completely depends on the artist’s will.

Most of the images that caught Joo’s attention through reflection and overlapping are foreign models that appear in advertising posters. In most cases, they are presumed to be the images of advertising models for fashion, accessories, cosmetics, etc. Since the artist of Urban Landscape did not choose the models’ poses, facial expressions, and makeup, the women's appearance follows the prototype of general advertising strategies. They are considered the so-called stereotypes of beautiful and elegant women. The abundance of images of “fascinating”female models in the city means that it also coincides with the sentiments of the urban crowd. This can be interpreted as a natural look in the eyes of an artist who has continuously documented the process of “foreign-style”modernization that Korea has been going through since the 1960s. This is also an unavoidable result of advancement of capitalism. Thus, the female images “produced” by foreign capitalism show how they are blended with the real city of Seoul by the process of overlapping. In that respect, Urban Landscape is an extension of his past works despite the changes in the form.

Third, they deal with combination of nature and culture. The corresponding images demonstrate the abstract form created by the deterioration of the paint on the walls and floors of the city over time. With the progress of weathering and erosion, paint to cover the gray concrete or many symbols marked at different corners for efficient communication in a crowded city are transformed into unexpected shapes. It is a surprising image created by cultural activities mixed with the power of nature. Most of the time, the form leads to an abstract image. Then why would the artist have paid attention to such images of “trivial” insignificant peeled paint or the “remained” paint?

Perhaps it is because the images are most easily visible in the city. The city is uninterruptedly pouring paint to achieve efficiency of communication among the numerous crowd, to carry out urban preservation and regeneration, and hide the gray color of the concrete. The action does not aim at a concrete figuration, so it is done “roughly” in general. Destruction of nature is made in the same direction. This means that the action does not distinguish elements to be erased and deleted. Such “transformed” figurations, namely, the newly “created” ones do not show any concreteness. They will just remain as an abstract image. In the end, the city is covered with countless abstract images that have been come into being this way. As long as the city continually repeats the mechanism of construction, destruction, and regeneration, the abstract images continue to undergo the process of transformation and generation.

4.

On the other hand, it seems that Joo’s interest in such abstract images originates from his desire of engaging himself in a “new” work, namely the uninhibited photography work without being bound to existing norms. Regarding this issue, it is important to consider not only the artist's long journey of photography but also the historical context of Korean photography. The 1960s, when the early works of Joo began, was a period in which the influence of photography focused on everyday life that had been established as the “mainstream” of Korean photography since the 1950s was still present. Photography focused on everyday life is a photographic movement developed based on the spirit of realism aiming to recording the reality in a honest manner. Out of this context, Joo accepted “realism” and “documentary” as the essential aesthetics of photography. Of course, realism was not the only vision that Korean photography represented during this period. Even though other attempts in pursuit of the so-called modernist photography also existed, the achievements were minute. Realism photography represented by photography focused on everyday life encountered its limits. Photography focused on everyday life evidently showed the possibility of new aesthetics to photographers while going through the Liberation and the Korean War. In particular, for photographers who were accustomed to the so-called “salon photography” tradition prior to the Liberation, the disaster of the Korean War awakened the awareness of people in the sense that photography ought not to forget the spirit of realism. However, photography focused on everyday life failed to go beyond the limits of the contest-oriented system. This led to preservation of stereotyped form or maintaining a narrow subject, accelerating the path of decline. The documentary work in the form of a photo essay that Joo showed in The Mixed Names and in the form of planned coverage that he tried in magazine photos afterwards is evaluated as an extraordinary achievement that broadened the language of recording beyond the limits of photography focused on everyday life and realism. During this process, Joo’s “aesthetic documentary” has become his own style.

Joo Myung Duck beliefs in “realism” and “documentary” from the early stage originate from his acceptance of the attributes of photography that is inevitably inseparable from a specific object. As a result, this is connected to acknowledgment of the inherent aesthetics of photography of which the “artistic value” of photography is in its attributes. This fact has being working as the norm for Korean photography for a long time after going through photography focused on everyday life and realism. However, according to this norm, photography is inseparable from a specific object so the photographer is not able to intervene in the “making” of the object. While contemporary art explores the abstraction of forms in various ways, photography had no choice but to deal with objects that exist in reality. Then, is it impossible to obtain the abstraction of photograph by depending on “document”? In fact, the Black Landscape close to monochrome in Lost Landscape is a sort of abstraction as well. We can understand that an attempt toward abstraction began in this work where the shapes of trees and grass are covered in black tones yet with the hardly visible appearance. Nevertheless, it is difficult to regard the Black Landscape as complete abstraction. It is because external shape such as leaves and branches still remain. In other words, abstractions are not realized unless things are driven out of the canvas.

In the series of Abstract, Joo Myung Duck starts to face the problem of abstraction in earnest. Through this work, Joodiscovers the possibility of how to obtain abstraction without giving up the methodology of “document” The method is remarkably simple. Abstraction comes out easily when getting closer to the paint marks on the wall or road floor. As soon as an object is separated from other objects or the surrounding background, the intrinsic shape of its own loses its power. Therefore, it is not possible to figure out what kind of object is displayed by the each image of Abstract. In other words, we will never know what was photographed, where the picture was taken, or what its original form was. The images sometimes appear in the form of a grid as in the Abstract Expressionism, and sometimes they look like an All-over painting using Jackson Pollock's dripping technique to sprinkle paint. In addition, there are a variety of forms of brush strokes that can be found in contemporary abstract art. However, the abstract image in Abstract was formed spontaneously through “collaboration” between nature and artificiality, and not painted or making by himself. Joo “simply” captured the image. What kind of capture could it be?

When looking at urban walls and streets from a daily perspective, an abstract form like the image in Abstract does not come into sight. It is because the human eye first sees the whole. Once we become interested in parts of the whole, we begin to see things as parts. Thus, perceived objects are supposed to have specific figure. Abstract forms are rarely perceived. Therefore, we can understand that the artist showed high interest in the abstract images appeared in Abstract and looked for them. This requires thorough observation and careful attention to separate parts from the whole. Moreover, it is vital to decide “how to” remove that part in accordance with compulsory feature of the mechanical device as a camera. At the same time, it is crucial to consider the division and proportion of the surface, and decide the magnitude of area to include the scattered dots and stains on the canvas. In the end, the capture in Abstract is not greatly different from the way abstract painters compose the canvas. Of course, some difference does exist. In order to achieve successful capture in photography, it is essential to solve the problem of having to intervene the artist's perspective in the structure determining the image as a whole. A reasonable compromise is necessary. Since it is not possible to transform the whole, careful attention and high judgment are required for frame composition to obtain the best abstraction effect. Abstract is a joint work between this comprehensive judgment and aesthetics.

Urban Landscape and Abstract are new attempts in light of the entire work journey of Joo Myung-duck. It is because he has maintained the perspective of “document” since his early work. In this regard, the “extraordinary” vision observed in his urban photography symbolizes change. The same happens to Abstract as well. His interest is no longer in the concreteness of the document. However, this change does not necessarily mean discontinuation from previous works. What he wanted was to see the city again. That is all. Seoul in the 1960s and 1970s is visibly different from Seoul in the 2000s. In other words, Joo simply catched Seoul as a much more dynamic and ever-changing city than the past time. That is to say, his “extraordinary” vision that appears in the urban work of the 2000s is a natural result. In this respect, Joo's city is a work that is elaborately combined between the perspective of an “thinker” with that of a “archivist” ◼️Park Pyeong Jong (Aesthetic and Photography Critic)

[1] Dansaekhwa means ‘monochrome painting’ in Korea.

1.

『서울』은 주명덕이 반세기 동안 도시 서울을 기록한 작업을 정리해서 보여준다. 1960-70년대의 작업을 모은 1부와 2000년대 이후의 작업을 정리한 2부는 한눈에 보아도 확연히 구분되는 차별성을 갖는다. 60-70년대는 주로 인간에, 2000년대 이후는 주로 도시 공간에 관심이 집중되어 있으며, 카메라 워크와 작업 형식에도 큰 차이가 있다.

1960-70년대의 서울은 한국전쟁 이후 폐허가 된 도시의 복구와 급속한 개발이 동시에 진행되던 시기다. 따라서 전쟁의 상흔과 전통의 흔적, 개발의 생채기가 도시 곳곳에 뒤죽박죽 섞여 있다. 실상 1960년대는 주명덕의 작업여정에서 소위 ‘습작의 시기’에 가깝다. 작가의 대표작으로 평가받는 <홀트씨고아원>전(1966)과 비슷한 시기의 작업이지만 명료한 문제의식과 완성도 높은 형식을 취한 이 포토에세이와 달리 60년대의 서울작업에서 작가는 자신이 배워 온 다양한 사진의 문법들을 적용, 실험하고 있다. 여기에는 1950년대에 전쟁 직후의 ‘생활상’을 진솔하게 담아내고자 했던 생활주의사진이나 리얼리즘사진의 유산도 미미하나 남아있고, 서양의 사진화보 잡지를 통해 광범위하게 배포되던 포토저널리즘이나 다큐멘터리 사진의 영향도 보인다. 나아가 60년대 <현대사진연구회>의 일원으로 활동하면서 ‘학습’했던 조형주의 사진의 형식적 요소도 섞여있다. 구도와 빛의 처리, 기하학적 형태를 찾아내어 ‘조형성’을 강조하기 위한 의식적인 관점의 선택 등이 그 예다. 말하자면 60년대의 서울 작업에서 주명덕은 자신이 배웠던 대부분의 사진 형식을 자유롭게 시도하고 있다. 그만큼 다양한 시각이 혼재돼 있다는 뜻이다.

1970년대로 진입하면서 주명덕은 기획 취재 형식으로 분명한 주제를 설정하여 서울에 접근한다. 1970년대의 서울 작업에는 『월간중앙』에 발표했던 <한국의 가족> 연작이 주로 포함돼 있다. 이 연작의 주제는 60년대부터 진행된 산업화와 개발로 빠르게 해체되어 가는 한국의 가족제도다. 전통적인 대가족제는 농촌사회의 극히 일부에만 남게 되고 급속한 도시화 과정에서 핵가족제가 보편적인 가족형태로 자리 잡게 됐다. 또한 무분별한 도시계획과 신도시 개발의 와중에서 터를 잃고 쫓겨나는 가족도 생겨났다. 이 급격한 변화에도 불구하고 서울의 가족들은 묵묵히 희망을 갖고 일상을 살아간다. 주명덕이 기록한 1960-70년대 서울의 모습은 전쟁과 개발, 산업화라는 미증유의 격변기를 살아가는 사람들의 충실한 자화상이다.

2.

2000년대 이후의 서울에 대한 작업은 1960년대 이후 줄곧 그의 사진 스타일을 지배해 왔던 ‘전통적인’ 다큐멘터리 방식과 차별성을 갖는다. 초기 작업에 해당하는 <섞여진 이름들>에서부터 <한국의 가족>, <한국의 이방>, <한국의 공간> 등에서는 절제 있고 엄격한 중립적 시각이 사진 전체를 지배하고 있었다. 이는 그가 일찍이 사진을 ‘사실과 기록’의 관점에서 수용했기 때문이다. 그리고 이런 시각은 대부분의 작업에서 일관되게 지속되고 있다. 그러나 이 태도가 그의 작업을 ‘시각적 보고서’의 차원에만 머무르게 하지는 않는다. ‘주관적’ 기록이기 때문이다. 그리고 이 주관적 기록의 바탕에는 그만의 고유한 심미적 시선이 깔려있다.

2000년대의 도시 사진이 기존 작업과 갖는 눈에 띄는 차이는 기록의 관점에서 진행했던 기존 작업의 스타일에서 벗어나 있다는 점에 있다. 우선 역동적인 촬영 시점과 앵글의 선택이 눈에 띈다. 나아가 초점이 맞지 않거나 흔들린 이미지도 많아 이 작업에서 정보가치는 크게 중요치 않아 보인다. 또한 의도적인 중첩과 반영 효과를 자주 활용하고 있어 촬영 목표에 집중하고 있지 않다는 인상마저 풍긴다. 서울이라는 도시를 효율적으로, 즉 객관적 정보를 담고 있는 사진으로 기록할 의도는 별로 없었던 것 같다. 왜 이런 방식을 취한 것일까? 도시 사진을 모아 2008년 대림미술관에서 열린 전시 제목은 도시정경(都市情景)이다. 정경(情景), 요컨대 도시가 불러일으키는 정서가 중요하다는 뜻이다. 마음의 풍경이라고도 할 수 있겠다. 말하자면 도시가 자신에게 불러일으키는 감흥을 사진으로 옮겨낸 셈이다.

실상 주명덕의 기존 작업에는 역사가나 사회학자의 ‘탐구적’ 태도가 깔려있었다. <섞여진 이름들>에서는 한국전쟁에 관한 거대담론이 미처 보지 못했던 혼혈 고아 문제를 예리하게 들추어냈고, <한국의 가족>에서는 근대화라는 문명사적 전환기에 한국의 가족제도가 어떻게 변화하고 있는지를 유형별로 정리했다. <한국의 공간>은 급격히 진행된 ‘서양식’ 근대화 과정에서도 굳건히 남아있는 우리 공간의 전통적 아름다움을 보여주는 데 심혈을 기울였다. 이 모든 작업에서 그는 절제와 배려의 자세를 유지했다. 인간에 대해서는 휴머니즘과 존중의 태도를, 공간에 대해서는 과장과 수사를 멀리하고 대상에 충실하고자 했다. 그것으로 충분했기 때문이다. 그것이 주명덕의 심미적 시선 바탕에 깔려있는 윤리적 태도이기도 하다.

그런데 이제 도시정경에 와서 그런 태도에 변화가 생겼다. 이 변화는 시기적으로는 1990년대에 와서 구체화된 <잃어버린 풍경(Lost Landscape)>에서부터 이미 시작됐던 것으로 보인다. 한국의 자연을 보여주는 이 작업의 시각적 특징은 사진 전체가 온통 어둡고 검은 톤으로 덮여 있다는 점이다. 이른바 ‘검은 풍경’이다. 이 작업에서 본래의 나무와 풀, 산이 갖고 있는 형태는 어둠에 묻혀 간신히 모습을 드러낼 뿐이다. 시각적 특성만을 놓고 본다면 서양 모더니즘 회화에서의 모노크롬이나 한국의 단색화와 비견될만하다. 이런 특징은 1970-80년대의 작업과 비교할 때 형식주의의 차원에서 눈에 띄는 큰 변화다. 주명덕은 이 작업의 바탕에 깔려있는 의도를 다음과 같이 밝힌 바 있다. “조국이 갖고 있던 아름다운 자연환경과 전통, 사람들이 지니고 있는 소박한 마음을 내 사진을 통하여 이 모든 것을 잃어버린 세대들에게 남겨보려는 작업을 계속해 왔다”는 것이다. 말하자면 ‘기록’에서 출발했으나 그 의도는 조국 산천의 아름다움과 사람들의 소박한 마음을 사진으로 표현하는 데 있다. 그것을 ‘잃어버려’ 보지 못하는 세대에게 자신의 심미적 시선을 통해 그 아름다움을 보여주고 싶었다고 할 수 있겠다. ‘검은 풍경’은 결국 그의 주관적 시선, 심미적 시선이 드러나는 모습이다. 여기서 나무의 형태나 톤이 본래의 그것과 얼마나 일치하느냐는 중요하지 않다. 자신이 그렇게 본다는 사실만으로 족하기 때문이다. 말하자면 ‘검은 풍경’ 역시 정경, 즉 자연이 그에게 불러일으키는 정서를 반영한다.

3.

그렇다면 도시는 그에게 어떤 정서를 불러일으켰을까? 첫째, 역동성과 긴장감이다. 역동성은 어떻게 표현될까? 통상적인 눈높이 시점을 대신하여 로우 앵글로 쳐다보는 방법이 있다. 그리고 실제 고층빌딩으로 가득 찬 서울에서 건물의 모습 전체를 보려면 올려다보는 수밖에 없다. 그렇게 고개를 쳐들고 빌딩을 보면 하늘이 함께 보이고, 인공구조물 옆으로 배치된 자연을 가장한 거대한 가로수도 병치 상태로 시야에 들어온다. 그러나 그 모습은 자연과 인공이 서로 노려보는 형태로 적대적 긴장감을 유지하고 있다.

둘째, 반영과 중첩. 도시정경에서 가장 자주 등장하는 요소로 작가의 시선을 유달리 잡아끈 모습이다. 실상 현대 도시 건축에서 유리가 건축자재로 활용되는 비중은 매우 높다. 빽빽이 가득 찬 폐쇄적인 건축물의 공간 구조에서 막힌 시야를 열어주는 방법은 유리의 투명성에 의존하는 것밖에 없기 때문이다. 그리고 유리의 투명성은 현대미술에서, 예컨대 미래파 작가들에게는 가장 전형적인 현대적 시각경험을 제공하는 수단이었다. 실제 도시 바깥으로 나가면 인간의 거주 공간에서 시야가 막힐 일은 거의 없다. 그런데 유리는 투명성만 가진 물질이 아니다. 보는 각도에 따라 맞은 편 이미지의 반영도 있고 굴절도 있다. 따라서 유리는 투명한 건너편 이미지와 보는 자의 편에서 유리 표면에 반사된 이미지의 중첩 효과를 만들어낸다. 이 효과는 비현실적이기도 하고, 기이하거나 몽환적이기도 하며, 놀랄 만큼 아름답거나 괴기스럽기도 하다. 어쨌든 일상에서 만나는 평범한 시각적 경험과 크게 다르다. 그리고 그 효과는 보는 자의 의도와 무관하게 우연히 찾아온다. 그럼에도 불구하고 그 우연을 카메라로 포착하는 것은 순전히 작가의 의지에 달려있다.

반영과 중첩을 통해 주명덕의 시선을 잡아끈 이미지는 대부분 광고 포스터에 등장하는 서양의 모델들이다. 그리고 그 이미지는 대체로 패션, 악세사리, 화장품 등의 광고 모델로 추정된다. 모델의 포즈와 표정, 메이크업 등을 <도시정경>의 작가가 선택한 것이 아니기에 그 여성들의 모습은 일반적인 광고 전략의 프로토타입을 따르고 있다. 이른바 스테레오타입으로서의 아름답고 우아한 모습의 여성들인 셈이다. 이 ‘매혹적인’ 여성 모델의 이미지가 도시에 넘쳐난다는 것은 그 이미지가 도시 군중의 정서에 부합한다는 뜻이기도 하다. 60년대 이후 한국이 걸어 온 ‘서양식’ 근대화 과정을 꾸준히 기록해 온 작가의 눈에 이 모습은 어찌 보면 당연할 수 있다. 그리고 이는 자본주의의 고도화에 따른 필연적 결과이기도 하다. 이렇게 서양의 자본주의가 ‘제작한’ 여성 이미지는 서울이라는 실제 도시와 중첩을 통해 섞여 들어가는 모습을 보여준다. 그런 점에서 <도시정경>은 형식적 변화에도 불구하고 과거 작업의 연장선상에 있다.

셋째, 자연과 문화의 혼합. 여기에 해당하는 이미지는 도시의 담벼락과 바닥에 덮여있는 페인트칠이 세월의 흐름에 따라 훼손되면서 만들어 낸 추상적 형태를 보여준다. 잿빛 콘크리트를 덮기 위한 페인트칠이나 복잡한 도시에서 효율적인 의사소통을 위해 곳곳에 새겨 놓은 각종 기호들은 풍화와 침식이 진행되면서 예기치 않았던 형태로 변형된다. 문화적 행위가 자연의 위력과 섞이면서 만들어낸 뜻밖의 이미지인 셈이다. 그리고 그 형태는 대체로 추상 이미지로 귀착한다. 그런데 작가는 왜 이 ‘하찮은’ 벗겨진 페인트, 혹은 ‘남겨진’ 페인트의 형상에 주목했을까?

아마도 도시에서 가장 쉽게 볼 수 있는 이미지이기 때문일 것이다. 도시는 수많은 군중들 간 소통의 효율성을 위해, 도시 보존과 재생을 위해, 콘크리트의 잿빛을 감추기 위해 끊임없이 페인트를 부어댄다. 그리고 그 행위는 구체적 형상을 목표로 삼지 않기에 ‘대충’ 이루어진다. 자연의 훼손도 같은 방향으로 진행된다. 지우고 삭제할 요소를 가리지 않는다는 뜻이다. 그렇게 ‘변형된’ 형상, 결국 새로 ‘생성된’ 형상은 어떠한 구체성도 띄지 않는다. 추상 이미지로 남게 되는 것이다. 결국 도시는 이렇게 탄생한 무수한 추상 이미지로 뒤덮여 있다. 도시가 구축과 훼손, 재생의 메커니즘을 끊임없이 반복하는 한 추상 이미지는 계속해서 변형과 생성을 거듭해나간다.

4.

다른 한편으로 작가가 이 추상 이미지에 관심을 갖게 된 데는 ‘새로운’ 작업, 즉 기존의 규범에 얽매이지 않고 자유롭게 사진작업을 해보고자 하는 욕망이 바탕에 깔려있는 것 같다. 이 문제는 작가의 기나긴 사진작업의 여정과 한국 사진의 역사적 맥락을 함께 고려해야 한다. 주명덕의 초기 작업이 시작되던 1960년대는 1950년대 이후 한국사진의 ‘주류’로 자리 잡은 생활주의 사진의 영향이 여전히 남아있던 시기다. 생활주의는 현실의 삶을 진솔하게 기록하자는 리얼리즘 정신에 입각하여 전개된 사진운동이다. 주명덕이 ‘사실성’, ‘기록성’을 사진의 본질적 미학으로 수용하게 된 데는 이런 맥락이 깔려있다. 이 시기 한국사진에 리얼리즘만 있었던 것은 물론 아니다. 소위 모더니즘 사진을 지향하는 다른 시도들도 존재했으나 성과는 미약했다. 생활주의로 대표되는 리얼리즘 사진도 한계에 봉착해 있었다. 생활주의는 해방과 한국전쟁을 거치면서 분명 사진가들에게 새로운 미학의 가능성을 보여주었다. 특히 해방 이전의 이른바 ‘살롱사진’ 전통에 익숙해 있던 사진가들에게 한국전쟁의 참상은 사진이 리얼리즘 정신을 망각해서는 안 된다는 각성을 불러일으켰던 측면이 있다. 그러나 생활주의는 공모전이라는 제도의 한계를 넘지 못했고, 따라서 형식의 정형성에 갇히거나 편협한 주제에 매몰되어 쇠락의 길을 걷고 있었다. 주명덕이 <섞여진 이름들>에서 보여주었던 포토에세이 형식이나 이후 잡지사진에서 시도했던 기획 취재 형식의 다큐멘터리 작업은 이처럼 생활주의와 리얼리즘 사진이 봉착했던 한계를 넘어 기록의 언어를 폭넓게 확장시킨 뛰어난 성과로 평가받는다. 그리고 그 과정에서 작가의 ‘심미적 기록’은 하나의 스타일로 굳어갔다.

‘사실성’과 ‘기록성’에 대해 초기부터 작가가 가졌던 신념은 결국 사진은 필연적으로 구체적 대상과 분리될 수 없다는 사진의 속성을 수용한 데서 비롯된 것이다. 이는 사진의 ‘예술성’은 바로 그 속성에 있다는 사진 고유의 미학에 대한 인정으로 귀결됐다. 그리고 바로 이 점이 생활주의와 리얼리즘을 거쳐 오랫동안 한국사진의 규범으로 작용해왔다. 그런데 이 규범에 따르면 사진은 구체적 대상과 분리될 수 없기에 사진가는 형상의 ‘제작’에 개입할 수 없다. 현대미술이 형태의 추상을 다양한 방식으로 탐구하는 동안 사진은 현실에 존재하는 구체적 형상만을 다룰 수밖에 없었다. 그렇다면 ‘기록’에 의존해서 사진의 추상을 얻어내는 것은 불가능한가? 실상 <잃어버린 풍경>의 모노크롬에 가까운 ‘검은 풍경’도 일종의 추상이다. 나무와 풀의 구체적 형상이 검은 톤에 묻혀 간신히 모습을 드러내는 이 작업에서 추상을 향한 시도가 시작되었다고 할 수 있다. 그러나 ‘검은 풍경’을 온전한 추상으로 보기는 어렵다. 어찌됐든 나뭇잎이나 나뭇가지와 같은 구체적 형상들이 남아있기 때문이다. 말하자면 화면에서 사물을 몰아내지 않는 한 추상은 구현되지 않는다.

<Abstract> 연작에서 주명덕은 본격적으로 추상의 문제와 대면한다. 이 작업을 통해 작가는 ‘기록’의 방법론을 포기하지 않고도 추상을 얻어낼 수 있는 가능성을 본다. 방법은 의외로 간단하다. 담장이나 도로 바닥에 묻어있는 페인트 자국에 가까이 다가가면 쉽게 추상이 나온다. 하나의 사물이 다른 사물이나 주변 배경으로부터 분리되는 순간 자신의 고유한 구체적 형상은 힘을 잃게 되는 것이다. 따라서 <Abstract>가 보여주는 각각의 이미지가 어떤 사물인지 알 수 없다. 요컨대 무엇을 찍었는지, 어디서 찍혔는지, 본래의 온전한 형태는 어떠했는지 알 수 없다. 그 이미지들은 때로 추상표현주의 회화에 자주 등장하는 그리드 형태로 나타나기도 하고, 잭슨 폴록의 드리핑 기법을 활용하여 물감을 뿌려놓은 올오버(All over) 페인팅처럼 보이기도 한다. 그 외에도 현대 추상미술에서 찾아볼 수 있는 다양한 붓질의 형태들이 있다. 그런데 <Abstract>의 추상 이미지는 작가가 직접 그리거나 제작한 것이 아니라 자연과 인공의 ‘협업’을 통해 저절로 형성된 것이다. 작가는 그 이미지를 ‘단지’ 포획했을 따름이다. 어떤 포획인가?

일상의 시각으로 도시의 담장이나 길바닥을 볼 때 <Abstract>의 이미지처럼 추상화된 형태가 눈에 들어오지는 않는다. 인간의 눈은 우선 전체를 보기 때문이다. 그리고 그 전체의 일부에 관심을 갖게 되면서 부분으로서의 사물을 본다. 이렇게 지각된 사물은 구체적 형태를 지니게 마련이다. 추상적 형태가 지각되는 경우는 매우 드물다. 따라서 작가는 <Abstract> 작업의 추상 이미지를 관심을 갖고 찾아다녔다고 할 수 있다. 여기에는 전체에서 부분을 떼어내서 보는 면밀한 관찰과 주의 깊은 시선이 요구된다. 나아가 카메라라는 기계장치의 강제성에 부합하여 그 부분을 ‘어떻게’ 떼어낼 지도 결정해야 한다. 면의 분할과 비례도 고려해야 하고 산만하게 흩어져 있는 점과 얼룩을 어디서부터 어디까지 화면에 담아낼 지도 결정해야 한다. 결국 <Abstract>에서의 포획은 추상 화가들이 화면을 구성하는 방법과 크게 다르지 않다. 물론 차이는 있다. 사진에서 성공적인 포획이 이루어지려면 이미 주어진 전체 이미지의 결정 구조에 작가의 시각을 개입해야 하는 난제를 해결해야 한다. 적당한 타협이 필요한 것이다. 전체를 변형시킬 수는 없기에 효과적인 추상의 효과를 얻어내기 위해서는 프레임 구성에 면밀한 주의와 고도의 판단이 요구된다. <Abstract>는 그런 종합적 판단과 심미안의 합작품이다.

<도시정경>과 <Abstract>는 주명덕의 전체 작업 여정을 놓고 볼 때 새로운 시도에 해당한다. 초기 작업에서부터 줄곧 ‘기록’의 관점을 유지해 왔기 때문이다. 도시 사진에 나타나는 파격은 그런 점에서 변화를 상징한다. <Abstract> 작업도 그렇다. 그의 관심은 더 이상 기록의 구체성에 있지 않다. 그러나 이런 변화가 이전 작업들과의 단절을 뜻하지는 않는다. 작가는 도시를 다시 보고자 했을 뿐이다. 분명 1960-70년대의 서울과 2000년대의 서울은 다르다. 말하자면 그는 서울을 이전에 비해 훨씬 역동적이고 변화무쌍한 도시로 해석했을 따름이다. 즉 2000년대의 도시 작업에 나타나는 ‘파격’은 자연스런 결과다. 그런 점에서 주명덕의 도시는 ‘기록자’의 시각에 ‘해석자’의 시각이 맞물려 나온 작업이라 할 수 있겠다. ◼️박평종 (미학, 사진비평)

Interpreter’s Eye for Beauty: Seoul of Joo Myung Duck

1.

Seoul is a summary presenting the works of Joo Myung Duck that documents the city of Seoul for half a century. Part 1, which is a collection of works from the 1960s and 1970s clearly differs from Part 2, which is a collection of works from the 2000s onwards. In the 1960s and 1970s, the artist’s attention was mainly focused on humans. On the other hand, after the 2000s, his primary attention was paid to urban spaces. We can also find a big difference in camera work and the work format.

Seoul in the 1960s and 1970s was undergoing a period of rapid development and restoration of the ruined situation after the Korean War. Therefore, the scars of war, traces of tradition, and side effects of development are mingled at every corner of the city. In fact, the 1960s was rather considered the so-called “study period” in the art journey of Joo Myung Duck. Unlike the photo essay from a period similar to that of Harry Holt Memorial Orphanage (1966, Jung-ang Gongbo-gwan, Seoul), which is evaluated as the artist's representative work, yet with a clear critical mind and high degree of completion, the artist applies and try a variety of grammars of photography, in his works of Seoul of the 1960s. In the works of the 1960, we can perceive the slightly remained legacy of photography focused on everyday life and realism photography, which the artist tried to capture “the way of life” right after the war in the 1950s. Moreover, we can also discover the influence of photojournalism and documentary photography, which used to be widely distributed through western photo pictorial magazines. Furthermore, we can also see the presence of the formal elements of formative based on the composition photography, which the artist used to “acquired” while playing a role as a member of the Modern Photography Society in the 1960s. For instance, they include the conscious choice of perspective to emphasize “formative composition” by finding composition, treatment of light, and geometrical forms. In other words, in his Seoul-themed works from the 1960s, Joo is trying most of the photographic forms he had acquired in an uninhibited manner. It means that multifarious perspectives are mixed in the works.

From the 1970s, Joo starts to approach Seoul by establishing a clear theme in the form of planned coverage. The main works on Seoul in the 1970s included the series of Korean Family published in Monthly JoongAng. The theme of this serial work is based on the Korean family system, which undergoes rapid dismantlement due to industrialization and development since the 1960s. The traditional large family system remains only in a small part of rural areas, while the nuclear family system has been established as a universal family form during the process of quick urbanization. In addition, in the middle of reckless urban planning and new town development, some families were forced to leave their homes. Despite these drastic changes, families in Seoul lead their daily lives silently not losing hope. The images of Seoul in the 1960s and 1970s documented by him are self-portraits that faithfully show how people were living in the unprecedented tempestuous times of war, development, and industrialization.

2.

Joo Myung Duck‘s works on Seoul after the 2000s are different from the “traditional” documentary method that has been predominant in his photography style since the 1960s. In his early work The Mixed Names(Seoul;Seongmungak, 1966), Korean Family, Strangers, and Korean Space, the whole photos were chiefly in line with a moderate and strict neutral perspective. This is because the artist accepted photography from the perspective of “facts and records” from an early stage. This perspective has been maintained with consistency in most of his works. However, this attitude does not limit his works to the level of a mere “visual report.” It is because his works are “subjective” records. In addition, the basis of subjective records consists in the unique aesthetic perspective of his own.

The noticeable difference between urban photography from the 2000s and previous works can be found from the fact that it is distant from the style of previous works in terms of records. Above all, what stands out most is the choice of dynamic point of shooting and angle. In addition, since there are plenty of images that are out of focus or had been shaken, the value of information in this work seems to be of little importance. Moreover, the artist frequently uses the intentional overlapping and reflection effects, so the images even give us the impression that the artist is not concentrating on the goal of shooting. It seems that the artist did not have particular intention to record the city of Seoul in an efficient manner, in other words, as photos containing objective information. Then what would made the artist take this method? The exhibition of urban photos held at Daelim Museum in 2008 is entitled Urban Landscape. When it comes to a landscape, it means that emotion evoked by the city is important. It can also be interpreted as a landscape of the mind. In other words, the inspiration that the city arouses in the artist was transferred to the photos.

In fact, Joo Myung Duck's previous works were based on “inquiring” attitude of a historian or sociologist. The Mixed Names keenly revealed the issues of biracial orphans that the metadiscourse about the Korean War failed to discover. On the other hand, Korean Family is a collection arranged by type how the Korean family system is undergoing changes during the transitional period of civilization called modernization. Korean Space focused on how to show our country’s traditional beauty of space, which preserved the firm posture even in the rapid process of “Foregin style”modernization. In all of these works, he maintained an attitude of moderation and consideration. Regarding to humans, he tried to display humanism and respect. At the same time, in relation to space, he made an effort to be faithful to the object while avoiding exaggeration and rhetoric. It is because that was simply enough. This is also the ethical attitude underlying his aesthetic perspective.

However, when dealing with Urban Landscapes, this attitude has changed. It seems that this change has already started with Lost Landscape, which had shaped in the 1990s. The visual characteristics of this work showing the nature of Korea consist in the fact that the entire photo is covered in dark and black tones. We call this the “Black Landscape”. In this work, the original forms of trees, grass, and mountains are surrounded by darkness with slightly visible aspects. From the perspective of visual characteristics alone, it is comparable to the monochrome in foreignmodernist painting or Dansaekhwa[1]. Such characteristics are considered a evident change in terms of formalism compared to the works of the 1970s and 1980s. Joo Myung Duck once expressed his intention underlying this work as follows: “Through my photos, I have been constantly carrying out works in order to leave the beautiful natural environment, traditions of my motherland, as well as the simple and pure heart of our people to the generations who had lost all of these. In other words, it started with “records,” but it intends to express the beauty of mountains and streams of the motherland and the simple and pure heart of the nation through photography. It can be interpreted that the artist wished to show the beauty through his aesthetic perspective to the generations that failed to see by “having lost” them. The Black Landscape is, in the end, the aspect manifesting his subjective and aesthetic perspective. It does not really matter how precisely the shape or tones of the tree correspond to its original facet. It is because it is enough that he himself sees it that way. At the same time, the Black Landscape also reflects the emotional landscape, in other words, the emotion that nature evokes in him.

3.

Then what kind of emotions would the city have evoked in Joo. First, they can be dynamics and tension. How can dynamics be expressed? There is a way of looking at a low angle instead of the usual eye-level viewpoint. To see the entire facet of buildings in Seoul full of skyscrapers, all we can do is to look up to see them. If we look at the building raising our head, we can see not only the sky as well, but also a huge street trees disguising as nature placed next to artificial structures in a juxtaposed state. However, it maintains somewhat hostile tension in the form of which nature stares at artificiality.

Second, the emotions lie in reflection and overlapping. Such elements appear most frequently in the Urban Landscape, and they particularly attract the artist's attention. In fact, glass makes up a large proportion as a building material in modern urban architecture. It is because the only way to open the blocked view in the spatial structure of a closed building that is tightly packed is by depending on the transparency of glass. In addition, for futurist artists, the transparency of glass used to be a means of providing modern visual experience as the most typical pattern in contemporary art. If fact, if we go outside the city, our visibility is hardly blocked in the residence spaces. However, glass is not just a transparent material. Depending on the angle from where we see, there is reflection or refraction of the opposite image. Therefore, glass creates an overlapping effect of the transparent image on the other side in addition to the image reflected on the surface of the glass on the side of the viewer. This effect can be unrealistic, strange, dreamlike, strikingly beautiful or grotesque. In any case, the effect is considerably different from the visual experience we usually encounter in our daily life. In addition, the effect takes place by chance irrespective of the viewer's intentions. Despite this, whether the artist captures this coincidence with the camera or not completely depends on the artist’s will.

Most of the images that caught Joo’s attention through reflection and overlapping are foreign models that appear in advertising posters. In most cases, they are presumed to be the images of advertising models for fashion, accessories, cosmetics, etc. Since the artist of Urban Landscape did not choose the models’ poses, facial expressions, and makeup, the women's appearance follows the prototype of general advertising strategies. They are considered the so-called stereotypes of beautiful and elegant women. The abundance of images of “fascinating”female models in the city means that it also coincides with the sentiments of the urban crowd. This can be interpreted as a natural look in the eyes of an artist who has continuously documented the process of “foreign-style”modernization that Korea has been going through since the 1960s. This is also an unavoidable result of advancement of capitalism. Thus, the female images “produced” by foreign capitalism show how they are blended with the real city of Seoul by the process of overlapping. In that respect, Urban Landscape is an extension of his past works despite the changes in the form.

Third, they deal with combination of nature and culture. The corresponding images demonstrate the abstract form created by the deterioration of the paint on the walls and floors of the city over time. With the progress of weathering and erosion, paint to cover the gray concrete or many symbols marked at different corners for efficient communication in a crowded city are transformed into unexpected shapes. It is a surprising image created by cultural activities mixed with the power of nature. Most of the time, the form leads to an abstract image. Then why would the artist have paid attention to such images of “trivial” insignificant peeled paint or the “remained” paint?

Perhaps it is because the images are most easily visible in the city. The city is uninterruptedly pouring paint to achieve efficiency of communication among the numerous crowd, to carry out urban preservation and regeneration, and hide the gray color of the concrete. The action does not aim at a concrete figuration, so it is done “roughly” in general. Destruction of nature is made in the same direction. This means that the action does not distinguish elements to be erased and deleted. Such “transformed” figurations, namely, the newly “created” ones do not show any concreteness. They will just remain as an abstract image. In the end, the city is covered with countless abstract images that have been come into being this way. As long as the city continually repeats the mechanism of construction, destruction, and regeneration, the abstract images continue to undergo the process of transformation and generation.

4.

On the other hand, it seems that Joo’s interest in such abstract images originates from his desire of engaging himself in a “new” work, namely the uninhibited photography work without being bound to existing norms. Regarding this issue, it is important to consider not only the artist's long journey of photography but also the historical context of Korean photography. The 1960s, when the early works of Joo began, was a period in which the influence of photography focused on everyday life that had been established as the “mainstream” of Korean photography since the 1950s was still present. Photography focused on everyday life is a photographic movement developed based on the spirit of realism aiming to recording the reality in a honest manner. Out of this context, Joo accepted “realism” and “documentary” as the essential aesthetics of photography. Of course, realism was not the only vision that Korean photography represented during this period. Even though other attempts in pursuit of the so-called modernist photography also existed, the achievements were minute. Realism photography represented by photography focused on everyday life encountered its limits. Photography focused on everyday life evidently showed the possibility of new aesthetics to photographers while going through the Liberation and the Korean War. In particular, for photographers who were accustomed to the so-called “salon photography” tradition prior to the Liberation, the disaster of the Korean War awakened the awareness of people in the sense that photography ought not to forget the spirit of realism. However, photography focused on everyday life failed to go beyond the limits of the contest-oriented system. This led to preservation of stereotyped form or maintaining a narrow subject, accelerating the path of decline. The documentary work in the form of a photo essay that Joo showed in The Mixed Names and in the form of planned coverage that he tried in magazine photos afterwards is evaluated as an extraordinary achievement that broadened the language of recording beyond the limits of photography focused on everyday life and realism. During this process, Joo’s “aesthetic documentary” has become his own style.

Joo Myung Duck beliefs in “realism” and “documentary” from the early stage originate from his acceptance of the attributes of photography that is inevitably inseparable from a specific object. As a result, this is connected to acknowledgment of the inherent aesthetics of photography of which the “artistic value” of photography is in its attributes. This fact has being working as the norm for Korean photography for a long time after going through photography focused on everyday life and realism. However, according to this norm, photography is inseparable from a specific object so the photographer is not able to intervene in the “making” of the object. While contemporary art explores the abstraction of forms in various ways, photography had no choice but to deal with objects that exist in reality. Then, is it impossible to obtain the abstraction of photograph by depending on “document”? In fact, the Black Landscape close to monochrome in Lost Landscape is a sort of abstraction as well. We can understand that an attempt toward abstraction began in this work where the shapes of trees and grass are covered in black tones yet with the hardly visible appearance. Nevertheless, it is difficult to regard the Black Landscape as complete abstraction. It is because external shape such as leaves and branches still remain. In other words, abstractions are not realized unless things are driven out of the canvas.

In the series of Abstract, Joo Myung Duck starts to face the problem of abstraction in earnest. Through this work, Joodiscovers the possibility of how to obtain abstraction without giving up the methodology of “document” The method is remarkably simple. Abstraction comes out easily when getting closer to the paint marks on the wall or road floor. As soon as an object is separated from other objects or the surrounding background, the intrinsic shape of its own loses its power. Therefore, it is not possible to figure out what kind of object is displayed by the each image of Abstract. In other words, we will never know what was photographed, where the picture was taken, or what its original form was. The images sometimes appear in the form of a grid as in the Abstract Expressionism, and sometimes they look like an All-over painting using Jackson Pollock's dripping technique to sprinkle paint. In addition, there are a variety of forms of brush strokes that can be found in contemporary abstract art. However, the abstract image in Abstract was formed spontaneously through “collaboration” between nature and artificiality, and not painted or making by himself. Joo “simply” captured the image. What kind of capture could it be?

When looking at urban walls and streets from a daily perspective, an abstract form like the image in Abstract does not come into sight. It is because the human eye first sees the whole. Once we become interested in parts of the whole, we begin to see things as parts. Thus, perceived objects are supposed to have specific figure. Abstract forms are rarely perceived. Therefore, we can understand that the artist showed high interest in the abstract images appeared in Abstract and looked for them. This requires thorough observation and careful attention to separate parts from the whole. Moreover, it is vital to decide “how to” remove that part in accordance with compulsory feature of the mechanical device as a camera. At the same time, it is crucial to consider the division and proportion of the surface, and decide the magnitude of area to include the scattered dots and stains on the canvas. In the end, the capture in Abstract is not greatly different from the way abstract painters compose the canvas. Of course, some difference does exist. In order to achieve successful capture in photography, it is essential to solve the problem of having to intervene the artist's perspective in the structure determining the image as a whole. A reasonable compromise is necessary. Since it is not possible to transform the whole, careful attention and high judgment are required for frame composition to obtain the best abstraction effect. Abstract is a joint work between this comprehensive judgment and aesthetics.

Urban Landscape and Abstract are new attempts in light of the entire work journey of Joo Myung-duck. It is because he has maintained the perspective of “document” since his early work. In this regard, the “extraordinary” vision observed in his urban photography symbolizes change. The same happens to Abstract as well. His interest is no longer in the concreteness of the document. However, this change does not necessarily mean discontinuation from previous works. What he wanted was to see the city again. That is all. Seoul in the 1960s and 1970s is visibly different from Seoul in the 2000s. In other words, Joo simply catched Seoul as a much more dynamic and ever-changing city than the past time. That is to say, his “extraordinary” vision that appears in the urban work of the 2000s is a natural result. In this respect, Joo's city is a work that is elaborately combined between the perspective of an “thinker” with that of a “archivist” ◼️Park Pyeong Jong (Aesthetic and Photography Critic)

[1] Dansaekhwa means ‘monochrome painting’ in Korea.

주명덕(朱明德, 1940~)은 황해도 안악에서 태어나 경희대학교 문과대학에서 사학을 수학하였다. 1966년 서울 중앙공보관에서 <포토·에세이 홀트씨 고아원>으로 첫 개인전을 열었다. 1968년부터 1973년까지 『월간 중앙』 사진기자이자 편집기획자로 활동하였다. 1979년부터 도서출판 시각을 운영하며 사진 작업과 다양한 출판 기획활동을 하였다. 1960년대 홀트씨 고아원, 미군기지촌 용주골, 인천의 중국인촌을 주목한 한국의 이방, 서울 시립아동병원 시리즈를 1970년대에는 한국의 가족, 지적 장애우 복지시설인 중앙각심학원, 서울 청운요양원과 서울 시립양로원, 서울 시립아동보호소, 미군기지촌 운천 등을 통해 사회적 다큐멘터리 작업을 하였다. 1970년대 중반부터는 한국의 공간, 명시의 고향, 한국의 장승 등 한국의 전통적인 공간과 건축의 아름다움을 담아내는 작업을 하였다. 1980년대부터는 자연과 도시를 주제로 작업하였으며 설악산, 오대산, 지리산, 한라산, 장미, 연꽃 등의 소재를 통해 ‘검은 풍경’ 연작을 선보였다. 한국사진역사 전시 운영위원장(1998), 사단법인 민족사진가협회 회장(1999-2003)과 제1회 대구사진 비엔날레 조직위원회 위원장(2006)을 역임하였다. 2010년 문화예술부문 파라다이스상을 수상하였다.

Joo Myung Duck(born 1940) was born in Anak, Hwang Hae Do, and studied history at Kyung Hee University, College of Liberal Arts. In 1966, the first solo exhibition was at the Central Public Information Center in Seoul as "Photo and Essay Holt's Orphanage." From 1968 to 1973, he worked as a photographer and editor for "Monthly Joongang." Since 1979, he has worked on photography and various publishing activities. In the 1960s, Holt's Orphanage, Yongjugol in the U.S. military base village, Bangbang in Korea, and Junggak Academy, a welfare facility for intellectually disabled people, Seoul Cheongun Nursing Home, Seoul Children's Shelter, and Uncheon in the U.S. military base village. Since the mid-1970s, it has been working on photographing the beauty of traditional Korean spaces and architecture, such as Korean space, the hometown of explicitness, and Korean Jangseung. Since the 1980s, it has been working on nature and cities, and has presented a series of "Lost Landscape" through materials such as Seoraksan Mountain, Odaesan Mountain, Jirisan Mountain, Hallasan Mountain, roses, and lotus flowers. He served as chairman of the Korea Photographic History Exhibition (1998), chairman of the National Photographers' Association (1999-2003), and chairman of the first Daegu Photographic Biennale Organizing Committee (2006). It was awarded Paradise in the Arts and Culture (2010) etc.

Joo Myung Duck(born 1940) was born in Anak, Hwang Hae Do, and studied history at Kyung Hee University, College of Liberal Arts. In 1966, the first solo exhibition was at the Central Public Information Center in Seoul as "Photo and Essay Holt's Orphanage." From 1968 to 1973, he worked as a photographer and editor for "Monthly Joongang." Since 1979, he has worked on photography and various publishing activities. In the 1960s, Holt's Orphanage, Yongjugol in the U.S. military base village, Bangbang in Korea, and Junggak Academy, a welfare facility for intellectually disabled people, Seoul Cheongun Nursing Home, Seoul Children's Shelter, and Uncheon in the U.S. military base village. Since the mid-1970s, it has been working on photographing the beauty of traditional Korean spaces and architecture, such as Korean space, the hometown of explicitness, and Korean Jangseung. Since the 1980s, it has been working on nature and cities, and has presented a series of "Lost Landscape" through materials such as Seoraksan Mountain, Odaesan Mountain, Jirisan Mountain, Hallasan Mountain, roses, and lotus flowers. He served as chairman of the Korea Photographic History Exhibition (1998), chairman of the National Photographers' Association (1999-2003), and chairman of the first Daegu Photographic Biennale Organizing Committee (2006). It was awarded Paradise in the Arts and Culture (2010) etc.

[SEOUL]

2022.5.20~5.30

옵스큐라

서울시 성북구 성북로23길 164

관람 시간 11:00-18:00 (전시 중 휴무 없음)

-별도의 초대일시는 없습니다.

[SEOUL]

2022.5.20-5.30

Gallery Obscura

164 Seongbuk-ro 23-gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul

Open 11:00-18:00 (no closing during exhibition)

-There is no special invitation.

2022.5.20~5.30

옵스큐라

서울시 성북구 성북로23길 164

관람 시간 11:00-18:00 (전시 중 휴무 없음)

-별도의 초대일시는 없습니다.

[SEOUL]

2022.5.20-5.30

Gallery Obscura

164 Seongbuk-ro 23-gil, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul

Open 11:00-18:00 (no closing during exhibition)

-There is no special invitation.